Shizuko Abe

An A-bomb Survivor as a Living Testifier

6. My Life after the War and Hibakusha Gatherings

After the war, it was difficult for my husband to get a job, because he had been an army officer. People didn’t want to hire ex-soldiers. He was working at a timber company run by our relatives. As he carried heavy timber, he got lower-back pain and could not work anymore. Then, he got a job at a prefectural office and worked until the compulsory retirement age. As my right fingers bent backward together, I could not use them. I worked in the fields and collected firewood using my left hand, but I had no choice but to ask my mother-in-law to do most of the house chores.

My first son was born in 1947, my second son in 1950 and my first daughter in 1954. It was said that hibakusha would have handicapped children, so when my children were born without any problems, I was very happy. My husband was enthusiastic about education. Although we were desperately short of money, he decided that all the children would go to college. As I could not work outside, we saved in every possible way for their education, and they all graduated from college.

As a hibakusha, I was severely discriminated against. My neighbors and my husband’s relatives said to me, “How dare you come back to Saburo without a divorce!” “Red demon!” On visiting days in my children’s school, I always bent my head down. I heard that my children were called a “child of Pika-flash.” At my son’s wedding, I looked down all the time. Also, other hibakusha who didn’t have any wounds or scars discriminated and gave me bad words. They were also hibakusha, but if their wounds were light, they looked down on other hibakusha who got seriously injured, let alone people who were not affected by the A-bombing. I was acutely aware that people never tried to understand others’ pain.

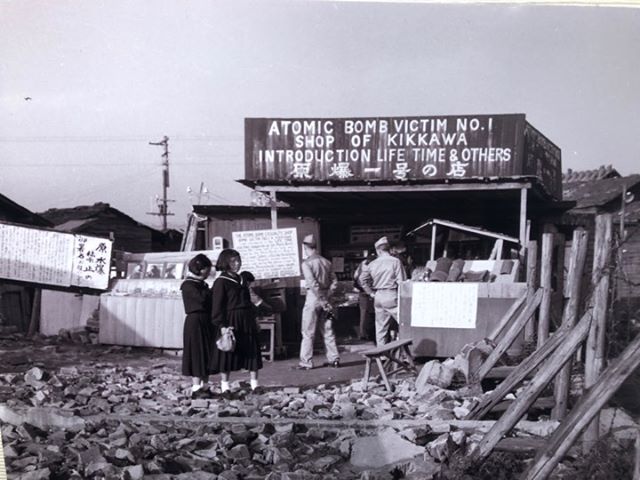

At a firework festival held two years after the A-bombing, I met Kiyoshi Kikkawa. He talked about the tragedy of the A-bombing, exposing his keloids to public view near the A-bomb Dome. He was called “A-bomb Victim No. 1.” There was a sign in front of his store no better than a shack, saying, “Come here hibakusha! Don’t hesitate to talk to me.”

I gathered my courage and talked to him. He said, “When you feel troubled, please come here. You can feel at peace just by sharing your suffering with other hibakusha.” I joined the hibakusha meetings a few times a year, where we spoke about our suffering and cried together. I also could laugh heartily in front of hibakusha who had the same experience. Ichiro Kawamoto, who built a shack next to Kikkawa’s, also joined the meetings and worked hard to support hibakusha. When Sadako Sasaki died, he made great efforts to build the Children’s Peace Monument with her classmates. He also established the Hiroshima Paper Crane Club. In that organization, he folded paper cranes with students of Jogakuin Girls School, donated them to monuments and brought them to hibakusha. They also donated thousands of paper cranes sent from home and abroad to the Children’s Peace Monument. I met Tokie, his wife, in the Peace Pilgrimage. I really enjoyed talking with them. I felt at peace just by getting together with other hibakusha and talking about our miserable situation. This kind of gathering might have taken place often, but my family was poor, and I could join it just a few times a year. I did not have money even for the train fare, and I walked all the way from Kaita to the meeting place. One time, we talked so much that I missed the last train and walked home. I remember this organization lasted about ten years.

In another meeting, Koichiro Tanabe, a writer we called “Tanabe-sensei,” opened his house to hibakusha and treated us several times a year. On New Year’s Day, his wife made sushi and mochi soup from Yamagata, his hometown. Every time, about ten hibakusha got together. Mr. Tanabe called for the Hiroshima city government to invite Yasunari Kawabata, the president of the Japan PEN Club and a Nobel Prize Laureate in Literature in 1968, to Hiroshima and ask him to transmit the horrors of the A-bombing to the world through the PEN Club. Accepting the invitation, Mr. Kawabata visited Hiroshima in 1949. He was shocked at the real situation of Hiroshima. The next year, he dispatched Japanese delegates to the PEN International meeting in Edinburgh, Scotland, to tell the tragic state of Hiroshima. Learning the plight of hibakusha, Ira Morris, the director of PEN International and his wife, Edita, worked hard as the leading members to open a “Rest House” for hibakusha in Ujina. They paid the house operation fees for a long time. Mr. Tanabe also recommended me to join the Peace Pilgrimage.