Shoso Kawamoto

Don't Forget about the A-bomb Orphans

2.After the Bombing, the Makurazaki Typhoon

August 6

We children were plowing the fields to plant sweet potatoes before going to school on August 6. When I looked up, I saw something unusual in the sky. In the direction of Hiroshima City, a gigantic column of white clouds like a thunderhead was rising up. As I had never seen a scene like this, I got very confused. I thought that the way the cloud welled up was strange. I talked to my friends, saying, “Look! What happened? What a giant cloud!” The A-bomb survivors often called the A-bomb “Pika-Don” (flash and boom). However, we didn’t sense the flash and the boom, because Kamisugi Village was located more than 50km away from Hiroshima City. The way the cloud welled up was so unusual that I wondered if something bad had happened, and I felt uneasy. Around 6:00 p.m. that night, news was sent to the village office, and what had happened was conveyed to our teachers later by the village office. The teachers then told us sixth graders that a new type of bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima. However, I didn’t have any concrete idea about what kind of damage the city had suffered or what the bomb had been like.

On August 7, in the evening, because the Geibi Line was opened that day, many families visited the temple to see their evacuated children. I asked those people about what had happened in Hiroshima, but no one answered my question. When a young man who lived near my house came to meet his brother, I asked him, “How is my house?” He only shook his head and didn’t tell me anything. I put together the stories I heard, which led to the conclusion that Hiroshima was destroyed completely by a new type of bomb. However, an entirely destroyed city was beyond my imagination. My friends’ families appeared one after another, and many of my friends left the evacuation temple. Only a dozen children remained there.

Hiroshima branch of the Bank of Japan

Photo by U.S. Army

Provided by Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

In the early afternoon of August 9, my sister Tokie, who was five years older, finally came to see me from Hiroshima. She said that she had been working inside the Hiroshima Station building at the time of the A-bombing. The station building collapsed, and she was trapped under it, but she managed to dig herself out. She was bruised but seemed to have escaped injury. The moment she saw me, she burst into tears without saying anything and explained the situation to me. On the day of the

A-bombing, she couldn’t enter the city center because of raging flames. Everything in the town had disappeared. The next day, she finally reached our house in Shioya-cho after the fire had died down. There was nothing left on the flattened land. There was no building like a landmark, so she walked along remaining streetcar lanes. Our house was in front of the Hiroshima branch building of the Bank of Japan, one of the ferro-concrete buildings which survived the A-bombing, so she could easily find it. But our house had completely collapsed. Around where the living room had been there were three charred bodies, cuddling each other. Their faces were totally burned black, which could not be recognized. However, she assumed from the place they were found that the bodies must have been my mother, my sister, Michiko, and my brother, Norihiro. Tokie asked soldiers, who were doing relief activities nearby, to have the three cremated. She collected their bones and then went to our uncle’s home in Tenma-cho with their bones. Our uncle’s house was also totally burned and broken, but he built a small shack to shelter from the weather as early as August 7 with the help from soldiers who had come to Hiroshima, by using materials such as wood he obtained around his house.

Tokie said that our father and Michiko, a second-year student of higher elementary school, had gone out for house demolition early in the morning. At that time, houses in the city were demolished in order to create a fire break to prevent important buildings and the whole city from burning by air raids. Toward the end of the war, everyone was under the national spiritual mobilization movement to serve for the country. No one could object, even when their own house was targeted to be torn down. In September, 1944, the first building demolition was carried out in Hiroshima. From August 1, the Sixth House Demolition was being carried out. On August 6, middle school students, girls’ school students and adults in the volunteer citizen corps from neighboring or outlying areas were engaged in this labor. About 6,000 students died during this mobilization. Tokie didn’t hear where our father or Michiko had been mobilized and didn’t know where they were.

After the A-bombing

I went back to Akiyaguchi Station on the Geibi Line with my sister. Beyond there, railways were not opened, so Tokie and I walked back to Hiroshima Station along the railroad tracks. Standing on the platform at Hiroshima Station, I couldn’t believe what I saw. There was nothing there! From the station, I could see the islands in the Seto Inland Sea. Before then, the sea was not visible because of many buildings standing in front of the station. We could hear no sound around us, and could see no one.

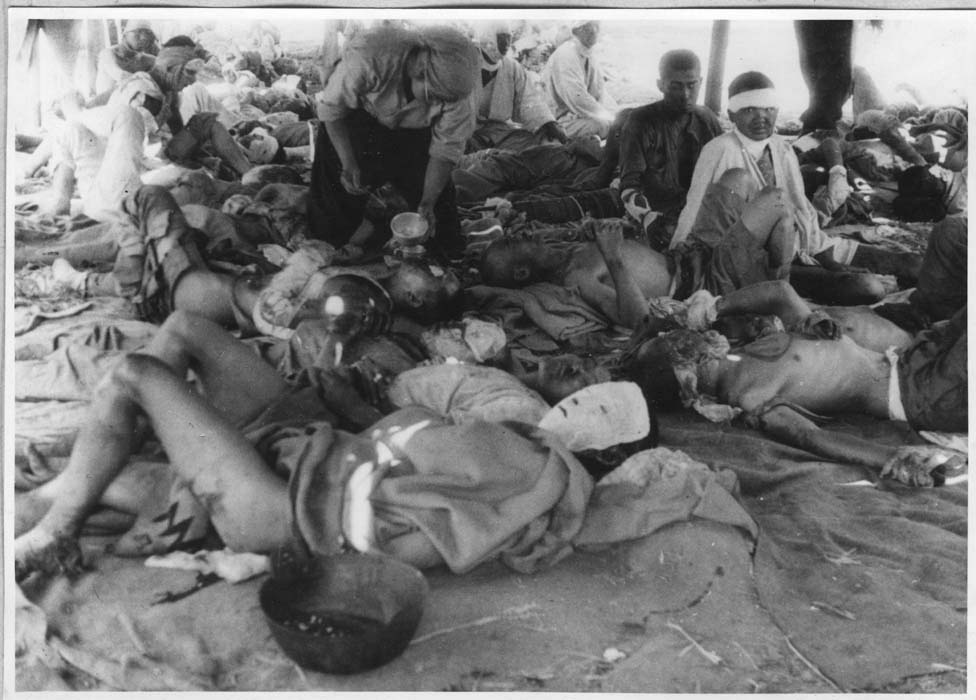

Inside an emergency relief station on the Ota River Embankment, August 9, 1945

Photo by Yotsugi Kawahara, 1100m from the hypocenter, Moto-machi

Provided by Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

I walked to our uncle’s house in Tenma-cho with my sister, and then we went to the Fukuromachi National School, which was used as a relief station, to look for our father and Michiko. Hundreds of injured people were lying on straw mats in a ruined building like an auditorium. Not a soul moved his body. We searched for Michiko and our father walking through those people, saying, “Is Tomeichi Kawamoto there? Does anyone know Michiko Kawamoto?” I felt sick from the smell in the relief station. It was beyond description. It was something mixed with the stench of dead bodies, blood, and pus. I couldn’t bear the smell and gradually got sick. Later, we also went to the Honkawa National School, but we couldn’t find them. I told Tokie that I couldn’t search any more, and stopped searching. Tokie continued to look for them alone for the next couple of days, however, she couldn’t find either of them. After a while, Tokie returned to work, and we never heard of them since then.

Fukuromachi National Elementary School, where I went to school, was located 460m from the hypocenter. At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, all of the 160 children in the first and the second grades, some upper-class children who had remained in the city, and 16 teachers, were outside getting ready for the morning assembly in the school grounds, and they died instantly in the A-bombing. I later heard that, by chance, at the time of the bombing, three children were in the basement where students changed shoes and miraculously escaped death. It is said that a little more than 8,600 children from the 36 elementary schools around the city were sent to live in the provinces away from their parents. About 2,700 of them were orphaned with no parents or no relatives to depend on. About 700 of those orphans were taken into orphanages, while the other 2,000 children were left on their own. More than a dozen children of Fukuromachi National Elementary School were orphaned and had to live on the street.

On August 15, the Imperial Rescript on Surrender was broadcast, and the war ended. I didn’t hear the speech. Tokie listened to it at work and was told that young girls should not go outside because U.S. soldiers might rape them. She didn’t go out of the shack for two days. However, soldiers in the Occupation Army were so kind, which was different from what we had heard, but I didn’t pick up chewing gum they threw from their vehicles. I didn’t feel like being given something by the people who had been our enemy up until recently.

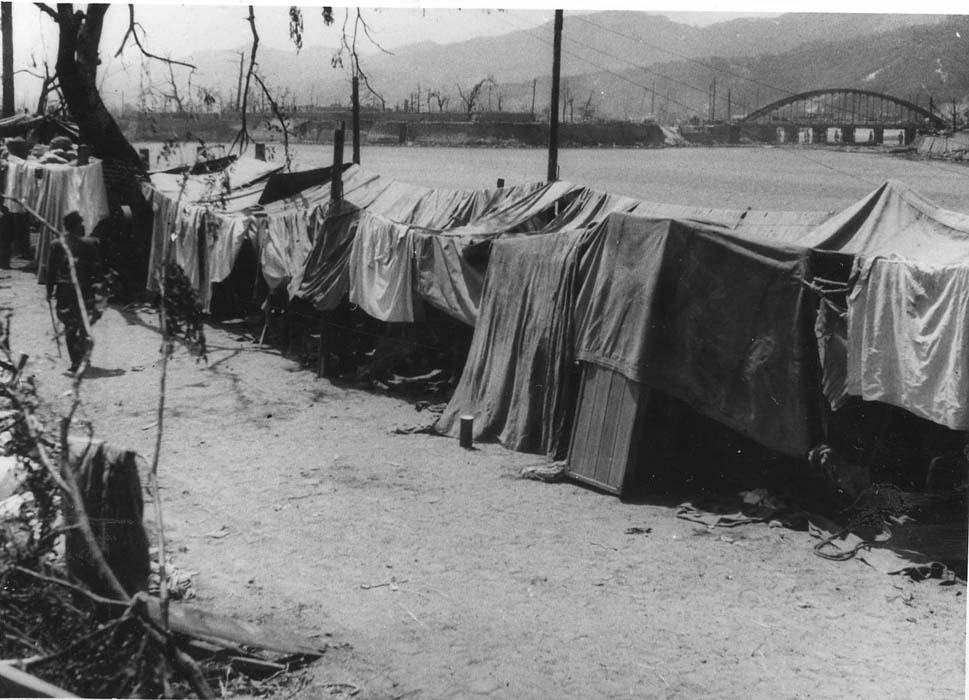

Inside an emergency relief station on the Ota River Embankment, August 9, 1945

Photo by Yotsugi Kawahara, 1100m from the hypocenter, Moto-machi

Provided by Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

A few days after the A-bombing, the city center smelled so terrible. No one could be seen and nothing could be heard. It was like a dead city. As Tenma-cho, where my uncle lived, was across the Tenma River away from the most severely damaged city center, we could barely live with less stench. At night, we saw bluish flames, called wild fire, flying unsteadily over the pitch-black town. It is said that the flames were caused by hydrogen phosphide emitted from dead bodies.

My uncle was the Chief of the Welfare Division of the city office, working to build shacks in Eba and Koi for relief workers just after the bombing. The shacks were poor, which were made by using materials collected from debris or wood from timber mills escaped from burning, and tin boards were just put on the top as roofs. Later on the the day of the A-bombing, my uncle had those workers build one six- tatami-mat shack for him. Tokie and I were allowed to live with him. He had no children and it was wide enough for him, his wife and us to sleep in.

Makurazaki Typhoon

On September 17, about one month after the end of the war, the Makurazaki Typhoon hit Hiroshima. This was one of the three biggest typhoons in the Showa era, along with the Muroto Typhoon of 1934 and the Isewan Typhoon of 1959. Hiroshima had been flattened because of the A-bombing, leaving only debris. The rainwater from the mountains washed into the city which had no protection, and the whole city was flooded with water. It is even said that the surface soil with residual radiation might have been washed away. Nationwide, there were 2473 dead and 1283 missing victims of this typhoon. Among these, only in Hiroshima Prefecture, there were more than 2000. However, there isn’t statistical data about how many wounded people were lying in the tents of the temporary first aid centers or how many people lived under the bridges in Hiroshima City after the A-bombing. It is also noted that more than 2000 people had died in Hiroshima City alone, but even now we don’t know the exact number.

Just after the A-bombing, elementary schools, company buildings, temples and shrines in the city were designated as first aid stations, but overflowed. Many people who could not move with serious injury were laid in temporary first aid stations which were built here and there on the river banks. Those emergency relief stations were so simple that ropes were just tied over frames and straw mats were draped over them, which could not have even been called a shack. The city was so devastated and full of debris that there was no space to put up tents. In addition, the water supply had been cut off, so relief stations were erected on the river banks so that water could be used. The largest emergency relief station consisting of hundreds of tents was on the Otagawa River (present Honkawa River) embankment, at the western side of the Hiroshima Second Army Hospital (present Motomachi, Naka ward). It was a long tent relief hospital which extended to both rivers’ banks (Motoyasu River and Honkawa River) of the present Peace Park. It is said that about 2000 people in those tents were all washed away by the flood. We learned later that many of the children, who had been left out on the streets and living under bridges, were engulfed by the flooding current. They are not included in the death toll. Professors and students from Kyoto University, who had come to Hiroshima to survey the bombed city and were staying in the Ono Army Hospital in Hatsukaichi, were covered by a mudslide.

My uncle’s shack in Tenma-cho survived the typhoon, but his relatives mobbed him. They had lived in their shacks in different places, which were swept away by the typhoon. My uncle and the relatives discussed what to do with us and suggested that I go to an orphanage and Tokie stay with them. Tokie was unwilling to leave me alone in an orphanage and refused the suggestion, so we left my uncle’s together. Tokie worked at the management section of Japanese National Railways, and we were lucky enough to use the employee lounge in Hiroshima Station to sleep. The room was screened off into two, and we lived in one half. Tokie worked every day, but I had nothing to do, so I began to wander around the city. I met many orphans who had lost their parents in the A-bombing and had no place to go, and collected iron scraps or cigarette butts with them in the ruins.