Masao Ito

From “Never Forget” to “Never Again”

3. Miserable Post-war Life

When the war ended, my father’s company lost its main business partner, the army, and he was forced to change jobs. In Takasu, where we lived, there were many fig orchards. My father got a hint from it and changed his business to making and selling fig jam. He might have felt responsible to protect the lives of his family and his employees. A big advertisement board saying “Ito’s Jam” could be seen from trains running beside the factory. Other than making jam, my father and my mother worked hard, doing a lot of things.

When I was a fifth grader, my father became unable to work. He was only 41 years old. He came down with the A-bomb disease generally called, “A-bomb Burabura Disease.” Later, this disease was named “Chronic Atomic Bomb Disease” by Dr. Masao Tsuzuki of the University of Tokyo. It is one of the aftereffects of radiation emitted from the atomic bomb, which appears several years after exposure among people without any visible injuries at the time of the A-bombing. This disease causes extreme fatigue due to weakened physical strength and resistance in a person. It is reported that the survivors consequently became unable to work and developed severe illness even from a slight illness. On the day of the A-bombing, my father entered the city center to help with relief activities on military orders. He also was near the hypocenter searching for Teruo and Ritsuko. After he returned home, he did not seem injured, but he became sick and never recovered from his bad health condition for 25 years. He died of liver cancer at the age of 66, after spending half of a year in the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital.

My mother had to take on the running of the company in place of my father while also taking care of our family. The business, however, began to fail like rolling down a slope and went bankrupt in 1956. I had just enrolled in Kanon High School in April of that year. One day, when I returned from school, I found red papers sealed on all of the furniture in our house, even on my desk, seizing all our property. Our family had to give up our house and factory and move.

In July, I dropped out of school, which I just entered, and began to work as a live-in worker for a food processing company. My family had begun to live in a shack, and I had no choice but to live in the company dormitory. I did hard manual labor from early morning to late at night, which was harsh for me as a 15-year-old. Less than half a year after I started to work, near the end of the 1956, a slight fever persisted every day. A health check in the hospital found that I was sick with pulmonary tuberculosis, and was hospitalized in a sanatorium in Moto-ujina. In those days, tuberculosis had no cure and was feared as a death-causing disease. The treatment was only rest and nutrition, so the patients just needed to eat nutritious food and relax. To me, it was like life in heaven with three meals and a nap.

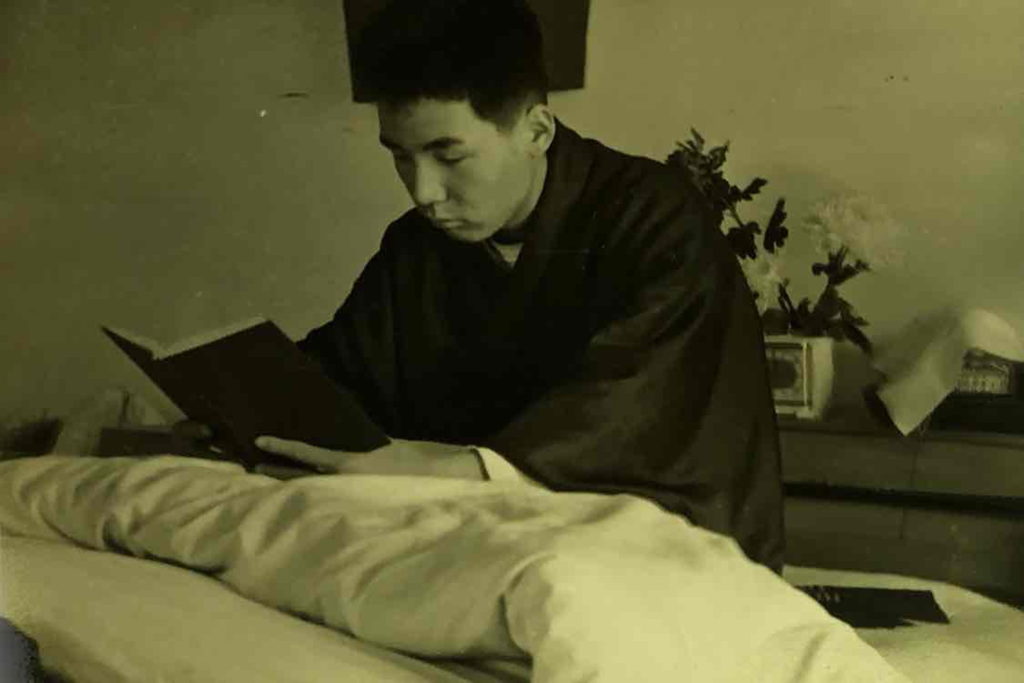

My disease was in the primary stage. Unlike hospitalized patients around me, I didn’t need to remove half of my lung, so I spent my time walking around the hospital grounds and reading novels in my room. I admit that I felt envious of my classmates who could enjoy their freedom. I wondered how they were enjoying skiing in winter, or how they were playing on the beach in summer. I liked reading. In the hospital, I read books written by Hyakuzo Kurata, Yuzo Yamamoto and Toson Shimazaki.

Two or three months after my hospitalization, a group in the U.S. sent streptomycin with a Bible to the hospital. Streptomycin was considered a specific cure for tuberculosis and a very expensive medicine. Since I was the only one given the treatment using this medicine, I think one of my cousins living in America sent it to me through the group. Administering streptomycin continued for half a year.

The Bible was written in both Japanese and English. and I started reading it soon. When I was reading, underlining the parts which drew my attention, my eyes got stuck by a verse, which said, “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute them” (Matthew 5:44). I flared up with anger with the verse and threw the Bible at the wall. To me, “enemies” meant the U.S. who dropped the atomic bomb, which killed many innocent citizens in an instant and destroyed our family. How can I love that country?

Streptomycin must have done me good because I completely recovered and left the hospital in the spring of 1958, almost one year after hospitalization. However, I didn’t have a house to return to. Since moving from our former house, my parents lived in a small shack, but there was no room for me there. My maternal grandmother felt sorry for me and took me in. She had four daughters, including my mother, her third daughter, and three sons. Her first and second daughters were married and living in the U.S., her oldest son died in war, her second son died young of cancer, and her third son worked for a company in Osaka. So, my grandmother and her youngest daughter stayed at the house. They took great care of me.

I went back to high school two years late. I had dropped out of school when I had finished the first term, so I started from the second term. My grandmother paid my tuition. About one year later, I noticed a church near our house. I began to go there every week without thinking deeply about it. It was ironic, considering that I had thrown the Bible at the wall in the hospital room. Half a year later, I got baptized to become a Christian. In the hospital, I read The Priest and His Disciples, written by Hyakuzo Kurata again and again, and I was hoping to become a Buddhist priest after my discharge. I think that it is not strange that I was attracted to Christianity, which has many doctrinal similarities with Jodo Shinshu (a sect of Buddhism).

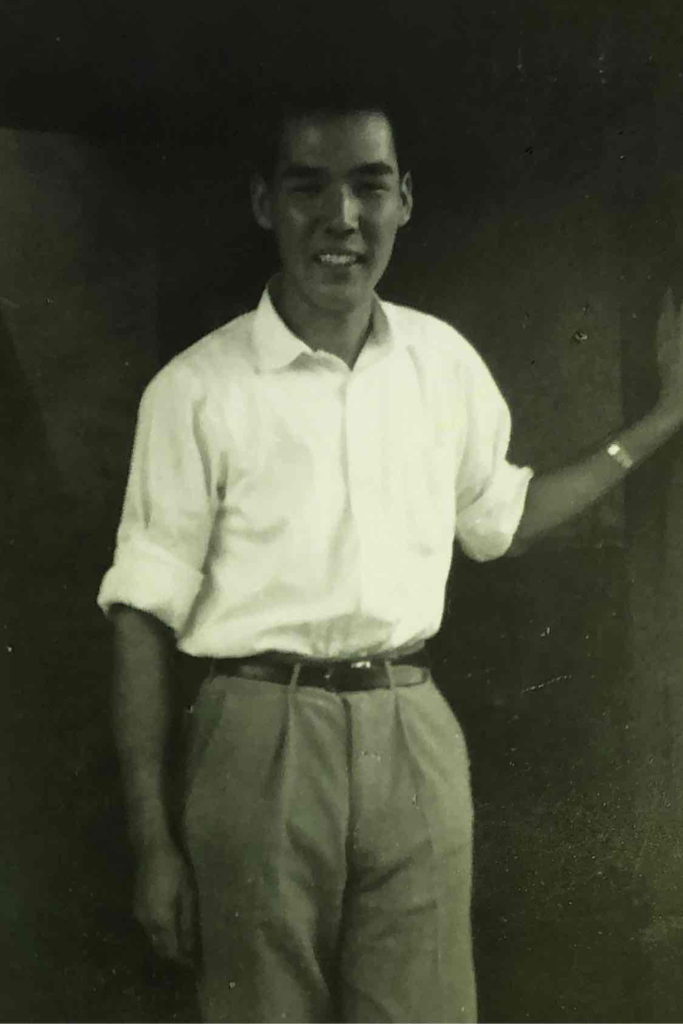

My grandmother supported me to go to college. I graduated from high school in 1961, entered Hiroshima College of Commerce (present, Hiroshima Shudo University) and graduated in 1965. After graduation, I entered a company in Hiroshima. I worked there until I retired in 2006 at the age of 65. That time overlapped with Japan’s economic boom, and I worked intensely as a hard-working employee.