Sadae Kasaoka

Losing both my parents all at once, I had no words to describe my loss

4. Life After the A-bombing

Although my sister, Sumiko, and her husband were living in Canada, my grandmother, Saijiro and I were going to evacuate the city to stay with her husband’s family in Kuchi, because of the scarcity of food in the city and for fear that Hiroshima might be air-attacked again. On August 14, my grandmother got a horse-drawn cart prepared in front of Yokogawa Station for us to go to Kuchi, and the three of us walked from our house in Eba to the station. On the way, seeing water gushing from a broken pipe by chance, I wanted to drink some and wondered off toward it. In the main street, people’s bodies had been cleared by the soldiers, but in the alley, I saw one dead body left there with his head lying in the water of a fire prevention water tank, even though more than a week had passed since the A-bombing.

As I was drinking water and looking around there, my grandmother and Saijiro didn’t bother to wait for me, and left on the cart for Kuchi. I didn’t know why they didn’t wait for me. They probably didn’t notice my absence. So, I had no choice but walk back home alone. My grandmother and Saijiro stayed in Kuchi for the next few months.

The next day, August 15, the Emperor’s announcement of Japan’s surrender was broadcasted. Kichitaro told me to listen to the broadcast carefully, saying that it would be an important one. So, I listened to the radio my hardest but was not able to catch anything because the radio sounded very noisy. I asked Kichitaro what the radio said, and he said indignantly, “Japan lost the war!”

A few days after that, a school friend of mine invited me to go to our school. While removing the debris of the auditorium, we found a dead body lying underneath it, even though it had been more than ten days since the A-bombing.

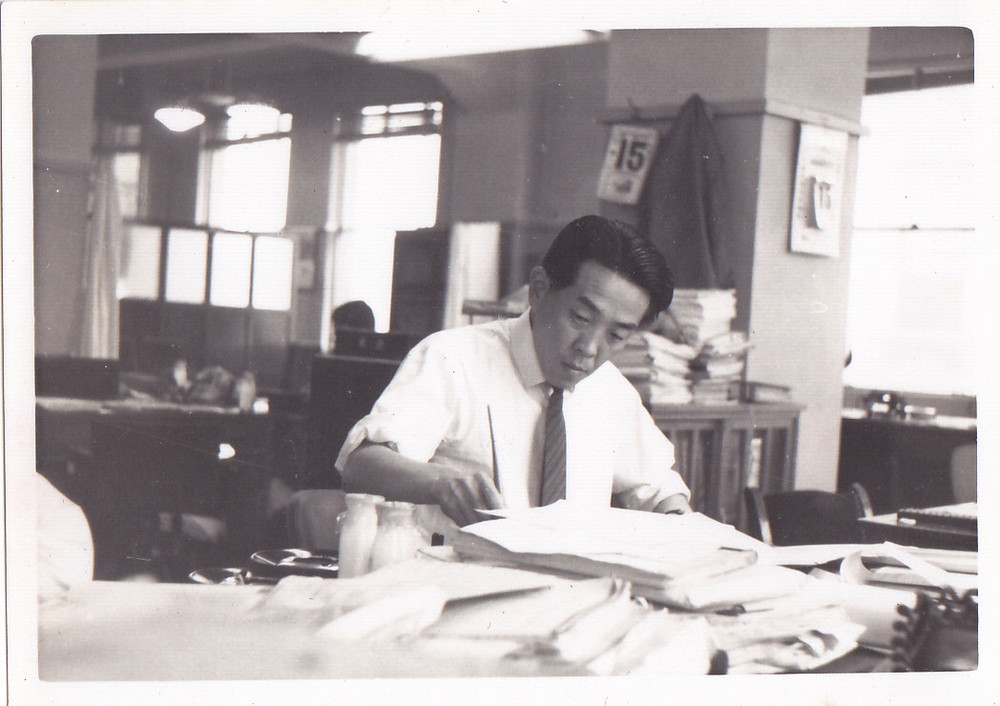

In order to support us in place of our parents, Kichitaro decided to give up his study at the Kobe Mercantile Marine School and went back to Kobe to submit his notice of leaving school. Coming back to Hiroshima, he soon got a job at the Maritime Administration Office (present Maritime Safety Agency.) Our life was difficult, so, to help him, I collected oysters along the nearby coast and figs in our fig field, and went around selling them.

Yoshie, Shinae and her husband, were worried about us and came to take care of us very often, even though they were living in Itsukaichi and Kobe. They even stayed with us for a while. Shinae’s husband came to see us all the way from Kobe almost every week. They did all the necessary paperwork for my grandmother, Kichitaro, Saijiro and me. For example, when I changed schools to the Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ High School (present Funairi High School), which was close to our house, Yoshie told me what to do for me to be able to change schools. Without her, I would probably have given up returning to school. The Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ High School lost 676 of its teachers and students, including all of its first- and second-year students.

Losing my father and my mother all at once, I had no words to describe my loss. When my friends casually said, “I went somewhere with my father,” or “My mother did something for me,” I felt very sad. The loneliest time was that whenever I got home saying, “I’m home!” I had no reply of “Welcome home, dear!” Unconsciously, I withdrew from chatting with my friends.

The Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ High School reopened in the middle of September. It was a school nominally, but in reality there was almost nothing left to be called a school. We started studying there, making the most of the ruins of the school buildings which had been heavily damaged and burned. We had no textbooks, so teachers used newspaper clippings to teach us Japanese. In Japanese dress making class, we make yukata, a Japanese summer kimono. Fortunately the school piano survived and we sang songs to the piano accompaniment.

With some effort, we repaired our tilted house to be able to continue to live in it. One day, a doctor and his family whose house and clinic burnt down in the bombing asked to rent our house and we agreed. Around the time when it was becoming cold, we moved into the nearby workshop shed which had been used for sea weed processing. The doctor said they would rent just for a short time, so we stored our furniture and household goods in our storehouse. A year later, they moved out.

My head injury of glass pieces gradually got well. Some of those glass pieces fell out of my head every time I brushed my hair. If I remember correctly, the injury healed around the spring of the following year. However, later in the summer, I developed skin rashes all over my body. Those rashes were fairly light with no pus except for three on my right upper arm. Those were serious and turned into boils. The boils about the size of a penny became bigger and bigger, and then broke open. Pus from the openings never stopped oozing out for six months. My grandmother explained, “Poison is getting out of your body.”

For a long time after the A-bombing, I didn’t like to talk with others and had a dark outlook. When I was 15 or 16, Kichitaro got married, and Tetsuko, 20, joined us. Until she came, we were a family of four, my grandmother in her mid-90s, Kichitaro, Saijiro, and me. My sisters in Itsukaichi and Kobe always came by and did almost every house chore for us. Saijiro was the happiest about his brother’s marriage. He loved Tetsuko as if she were his mother. I think she must have been very busy taking care of us. Then Tetsuko gave birth to a baby. Around that time, I think I became cheerful again.

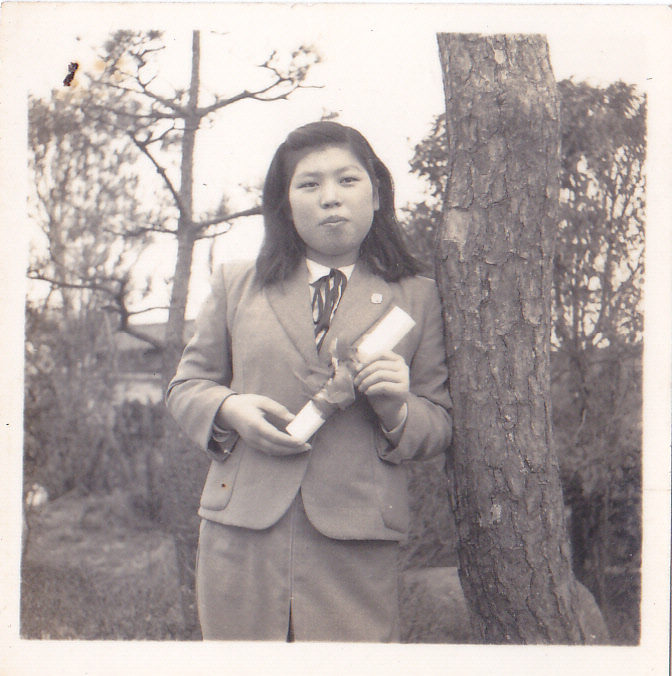

In the spring of 1948, I became a first-year high school student in the new education system, when I should have been a fourth-year student in the Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ High School. The new system of school years was six years for primary school, three years for junior high school and three years for high school. The name of my school was changed to Futaba High School, and the following year, the name was changed again to Funairi High School and became a school for both sexes. Though they hadn’t cared about them before, some girls with some keloids started to hide them from boys in embarrassment. On the contrary, the boys didn’t seem to mind theirs.

In 1951, I graduated from high school. I looked for a job, but I was turned down when it was discovered I was an A-bomb survivor. Finally, I got a job as a temporary worker of the Hiroshima Prefectural government. I had some marriage meetings, but I was turned down, too, because I was an A-bomb survivor. At that time, A-bomb survivors were discriminated against.

In 1953, I had my first annual medical check-up at the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (present Radiation Effects Research Foundation). Every year, a taxi came to my house and took me there. During the check-up, I was dressed only in a medical gown and was taken around to a room after another for physical examinations. Recently I had check-ups every other year. Every time I was told that I was anemic. I remember that it was very cold there in winter.

In 1957, when I was 25, I got married to Kenji Kasaoka, also a survivor. It was an arranged marriage, and we were soon blessed with a girl and a boy.

Kenji had been mobilized to work at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Kanon-machi (present Nishi-ku, Hiroshima) when the A-bomb was dropped. The following day, seeing fires of the city had subsided, he went searching for his father and his sister, both of whom were in the central area of the city at the time of the A-bombing. His father worked in Dobashi (600m from the hypocenter), and when Kenji went there, he found the pocket watch which his father always wore. So he collected some ashes of the body wearing the watch to bring them back home. His sister worked for a bank in Hatchobori (700m from the hypocenter). Kenji came across his sister’s co-worker who had fortunately survived the A-bombing. The co-worker said, “At that time, your sister was preparing tea in the kitchen,” but Kenji found no remains of his sister there. His mother was in her parents’ house in Kako-machi (1.2km away from the hypocenter, present Sumiyoshi-cho, Naka-ku, Hiroshima) when the A-bomb was dropped. She was blown out of the house about 30 meters.

In 1964, at the age of 35, Kenji was diagnosed with spinal cancer and passed away seven months after he got hospitalized. At that time his doctor said that he couldn’t tell if Kenji’s cancer was due to radiation from the A-bomb. Although I am not an expert about medicine, I am sure that his cancer is associated with the A-bomb because he walked around the area close to the hypocenter the following day, searching for his father and sister. After his death, I had to support my mother-in-law, my sister-in-law and my two little children.

I worked for the Hiroshima Prefectural government until my official retirement, and after that, I worked at the Hatsukaichi City Office and other offices as a counselor for A-bomb survivors until I was 79 years old. I am thankful to everyone around me that I have lived to this age.