Emiko Okada

The Atomic Bomb was Developed by Human Beings And Also Dropped by Human Beings

1. Life Before the Atomic Bomb

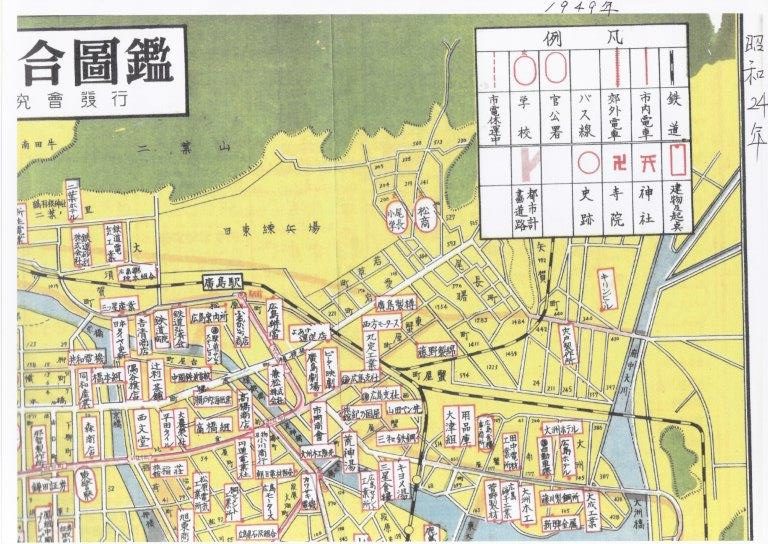

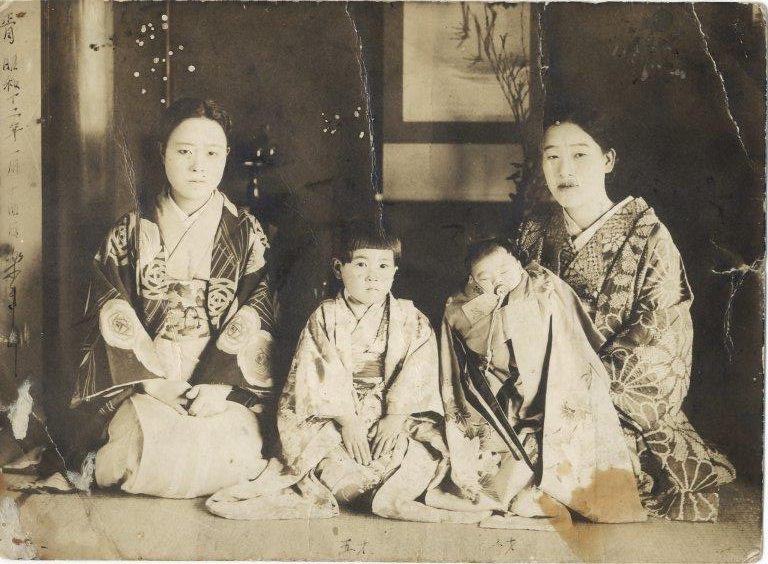

I was born on January 1, 1937, as the third child of my father, Shigemi and my mother, Fuku. Their eldest son died shortly after he was born, and my sister Mieko was four years older than me. I also had two younger brothers—Katsuyuki, three years younger, and Koso, five years younger than me. My house was located in Onaga-cho, in Higashi-ku, Hiroshima, 2.8km from the hypocenter, three doors down from the Matsumoto Commercial High School (now Setouchi High School). My father was a teacher there, and my mother was a full-time housewife.

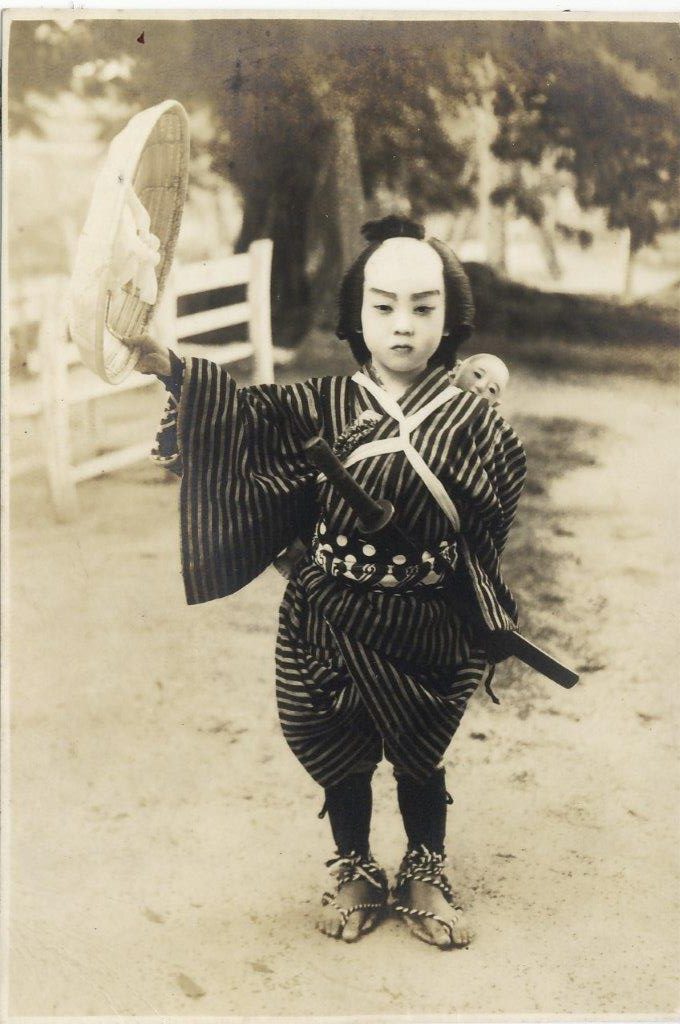

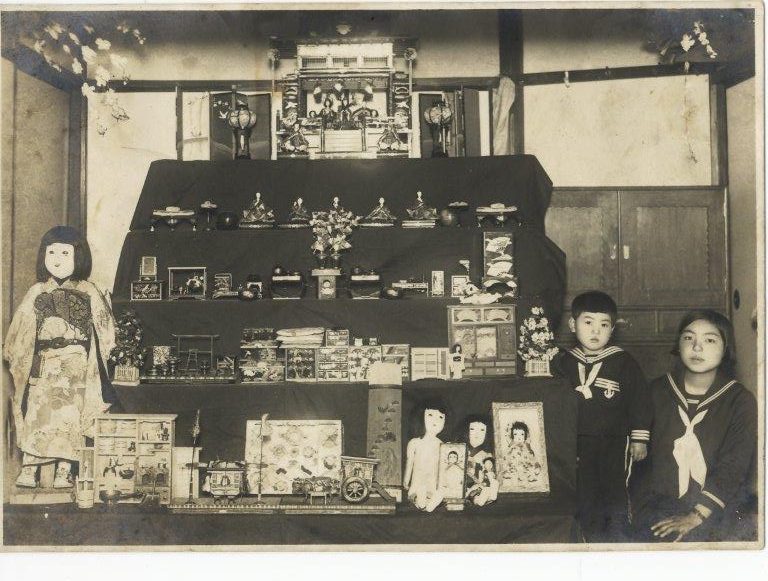

My sister and I learned Classical Japanese Dance from a young age, and we danced in front of wounded soldiers when we visited the Army Hospital at the West Military Drill Grounds. When I was little, I wished I could be a soldier. A boy’s dream back then was to become a soldier, and since I was a girl, not being able to become one was very frustrating to me. So I asked my mother to make me clothes similar to a navy uniform and even had my hair cropped short. There is a picture of me from back then with cropped hair.

In those days, boys and girls in Japan were not allowed to play together from an early age. However, I do have memories of playing with a boy from the neighborhood in the air-raid shelter dug in our garden. It’s such a fun memory how we hid and played, the boy playing the role of a father and me, the mother. Of course, once we were one step outside of the shelter, we couldn’t speak to each other. Even little children could not play freely, nor could we freely say hello to friends. Once outside of the house, we constantly lived life under tension from feeling watched all the time by our neighbors.

The Second Sino-Japanese War began in 1937, the year I was born, then the Pacific War started when I was four years old. My entire childhood was caught up in war, and we lacked all kinds of goods. Onaga-cho has seven shrines and temples, but all of their bells were contributed to the war effort, and there were none left in the town. Everything made of metal, such as gateposts and window frames, were all taken away. Food was no exception. We never had a chance to eat white rice. Cubed daikon radish or potatoes boiled in water was the staple food we ate in place of rice, and there were no side dishes to go with it. If we were lucky, we would have a small amount of pickled plums or Japanese leek. Boiling the daikon or potatoes was the chore of the children. Other chores for us included getting water for baths or blowing air into kamado (wood-burning stove) using a blowpipe until it was cooked. We were thankful just to have something to eat, and none of us complained. We were taught that “luxury was the enemy,” and that all goods first went to soldiers.

One day, two of the classrooms at Matsumoto Commercial High School were requisitioned by the army. At a fixed time every morning, I would hear the sound of the marching trumpet, and see students rushing to form a line in the schoolyard. All of them wore khaki uniforms that looked like military uniforms, with gaiters wrapped around their legs. Officers carried sabers and wore many golden rank insignia on their chest. I was very young and the officers were kind to me. When I would go to play, they would give me konpeito (tiny colored sugar candy). It was sweeter than anything I’d ever tasted before and so beautiful in color, that eating it felt like a dream. In the classrooms used by the officers, we could see many things we hardly ever saw, such as white rice, sugar, sake, etc.

In 1943, when I was six years old, I entered Onaga National School (present Onaga Elementary School). I remember receiving textbooks shortly after entering the school, but I have no recollection of studying in a classroom. We worked every day, plowing the schoolyard, making a garden of potatoes, squash, daikon radish, etc., and watering the vegetables every day. We also wrote letters to soldiers or went around the neighborhood asking women to be part of making the thousand-stitch belt to put into comfort bags to send to soldiers in the battlefield. A thousand-stitch belt was made of a thousand red stitch knots on white cloth embroidered by a thousand women, and worn by soldiers around their stomachs. These were considered to be a good-luck charm that would protect the soldiers from bullets. A few months before the A-bomb was dropped, around March, when I was playing with a few friends near the large water tank made on an elevated platform in the schoolyard, a Grumman fighter jet swooped down toward us. We just stood there, when strafing with machine guns suddenly opened up. I think their target was the East Military Drill Grounds, located in front of the school. The fighter jet, strafing low enough that I could see the pilot’s face, instantly engulfed the drill grounds in flames. Then it flew off in the direction of Hiroshima Station. One of the bullets hit the edge of the water tank and caused water to burst out. I heard that a woman had died from this attack. I was regularly taught the phrase, kichiku beiei, (“Americans and British were savages”), so I was extremely frightened.