Sadae Kasaoka

Losing both my parents all at once, I had no words to describe my loss

1. My background

I was born as the seventh child of my father, Shinajiro, and my mother, Kichi, on September 20, 1932. I had two elder brothers, four elder sisters and one younger brother. One of my sisters passed away by an accident at the age of four, and my eldest sister is 17 years older than me. Including my grandmother, our family members were ten. Our house was quite big, located in Eba-honmachi (Naka-ku, Hiroshima, 3.5km from the hypocenter). Though there are many houses there now, at that time there were just a few. My father’s elder brother emigrated to the U.S. and was very successful in business, owning a few department stores. His remittance to my grandmother allowed her to build such a big house where we lived.

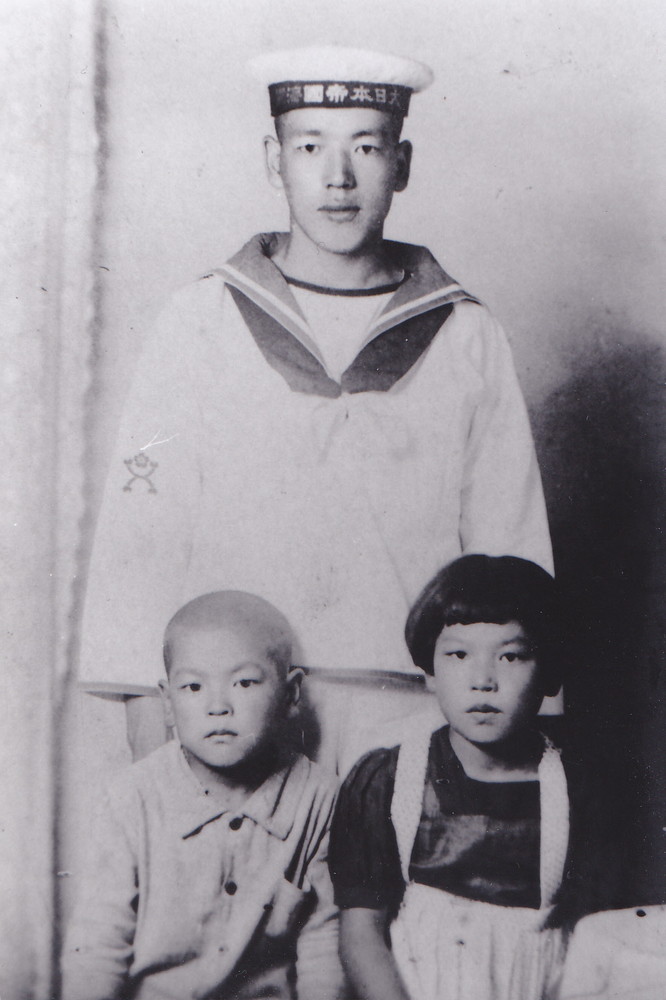

family picture

with my brothers

My parents grew barley and vegetables and made nori seaweed in winter. My father was a very kind man, respected as the leader of our neighborhood association. He often invited some of the young soldiers who were going to war to our house the night before their departure to comfort them. Every morning, my mother carried vegetables which she had grown by a two-wheeled cart and sold them in the city center. At that time, it was common that children took care of their younger siblings. Even when they went to school, they often carried their siblings on their backs. My parents were very busy, and they rarely had dinner with us.

I entered Eba Elementary School in April, 1939. To my surprise, most of the teachers were women, and only the young substitute teachers and older teachers were men. I didn’t like school, but I remember it was a fun time when I played with my friends in the warehouse for rice husks.

When I was a second grader, my eldest brother, 15 years older than me, was drafted and went to war. It was his second time to be drafted, and the convening place was Kure. Two years later, we received an official notice that he was killed in action on the aircraft carrier, Ryujo, bombed by the U.S. military in the Solomon Islands. At that time fallen soldiers were respected as having an honorable death. His funeral was held at the elementary school auditorium with all the neighbors in town. The sign of an honored family was put on our house. Now, I wonder how deep my parents’ sorrow was, losing their first son. However, they never cried in front of people, because we were told that a soldier killed in action to protect Japan was honorable.

When we had his memorial service, I was sent to my sister Sumiko’s in-laws house to get rice. Rice was strictly controlled by the government, and since my family didn’t farm rice, the only way to get rice was by ration. Military police could arrest adults carrying rice, so my parents thought the police wouldn’t think that a child like me would be carrying rice. Carrying a backpack, I took a train by myself to Akiimuro station on the Kabe Line and walked for many hours on a mountain path. Then I arrived in Kuchi (present Asakita-ku, Hiroshima), where my sister’s husband’s family lived. Children of those days walked a lot. At that time, my sister didn’t live there because she had immigrated to Canada with her husband. Rice was very valuable. We called a bunch of ten sheets of nori seaweed one jo, and we could exchange ten jos of seaweed for 1.5kg of rice.

During the war, we hardly had food to eat. When I became a sixth grader, students also started farming vegetables in our school yard. Children were forced to be patient with everything. Though we starved, we had to say that we didn’t want food until we won the war. There was a dumpling called Eba dango in Eba. People mixed yomogi leaves and rice bran and made the dumpling. It was not tasty at all, but we could eat it as a substitute for better food. Although we heard that the U.S. military had bombed many cities all over Japan, we children never doubted Japan’s victory. We thought it was a just war and that the kamikaze (divine wind) would absolutely help us to win.

I wanted to be a teacher, so I entered Shintoku Girls’ School in April, 1945. For one month after starting, we had several classes such as math, Japanese, manners and martial arts. In manners class, we learned how to open and close a fusuma sliding door and how to walk on tatami mats. In martial arts class, we were trained using bamboo spears. However, third- and fourth-year students soon were mobilized to military factories and first- and second-year students to farms or building demolishing site. We hardly had time to study. We worked every day, even during summer holiday. We pulled down designated buildings around important buildings to make firebreaks or widen roads that would prevent fire from spreading during an air raid.

Though our family members were ten, at that time we were only four at home—my grandmother (90), my father (50), my mother (49) and me (12.) My eldest brother was killed in action, and my three elder sisters were married. My eldest sister, Sumiko, emigrated to Canada; the second one, Yoshie, was in Kobe; and the third one, Shinae, lived in Itsukaichi (present Saeki-ku, Hiroshima) My second elder brother, Kichitaro, entered the mercantile marine school in Kobe, and my younger brother, Saijiro, a fifth grader, was evacuated in a group to Miyoshi, in the northern part of Hiroshima prefecture. Children from third graders to sixth graders, who lived in cities which might have air raids, were evacuated to relatives’ homes in the countryside. If they had no relatives, they were evacuated to temples or shrines in the countryside with their teachers. My brother told me that they didn’t have enough food, and they cried every evening, “I’m hungry! I want to go home!”