Lee Jong-keun

"Don’t stay silent!"--Raise your voice!

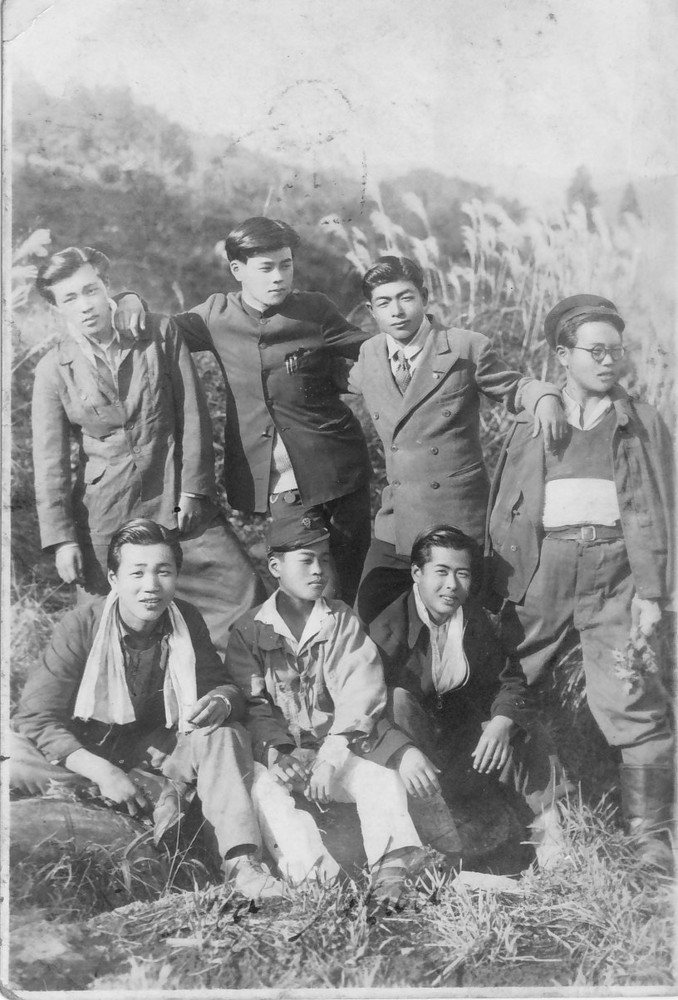

2. My childhood

I was born on August 15, 1928, in Hikimi. My father asked his brother living in Korea to report my birth to his legal address on the family registry as ordered. However, my uncle didn’t do so for one year because he thought I might not survive. At that time, so many infants died soon after their birth. That made my official birthday exactly one year delayed, August 15, 1929.

In 1935, my family moved from Hikimi to Yoshiwa, Saeki-gun, (present Hatsukaichi City) Hiroshima Prefecture. Yoshiwa is in a different prefecture but is located just across the prefectural border from Hikimi. He burned charcoal there, too. He also collected garbage and disposed the bodies and belongings of people who died of tuberculosis because Japanese people disliked doing those jobs. At that time, tuberculosis was feared as a fatal illness because there was no medicine for it and many people died of it.

Soon after we moved to Yoshiwa, I started going to a branch school of Yoshiwa Elementary School near our house. I enjoyed the first half of my elementary school life without any discrimination. However, from the fourth grade, I had to go to the main school four kilometers away. There, discrimination started against me. Children called me, “Korean!” which I had never been called at the branch school. Yoshiwa was a small village with about 400 households in total. Everyone knew where everyone else lived. Besides, there were few Korean people there. If my memory is correct, there were four families. I assume the reason that children called us “Koreans!” was that their parents talked about us at home. Children are not born to discriminate. I think that what parents say and do at home imprints discrimination into their children.

Mr. Suginohara, my homeroom teacher in the fourth and fifth grades, obviously targeted me to discriminate against. Whenever someone was crying in class, I was to blame, and the teacher slapped me, hooked my leg and knocked me down, and made me stand in the hallway. On a snowy day, he threw my lunch box out of the window because the lunch I was warming around the heater smelled like kimchi. I picked up and ate the food that scattered on the snow. When something bad had happened, other kids told teachers that I had done it, but actually I didn’t do anything. No classmates helped me out. There were three Korean children including me at school, one of whom was born to a Japanese and a Korean, and we made good friends.

When I was a sixth grader, on my way home from school, a man suddenly came out of his shop at the foot of a bridge in Nakatsuya, a community in Yoshiwa, and said to me, “Hey, Korean. Come here!” I came over to him. Then he said, “Stand here.” I stood in front of him. I was surprised and my heart was pounding. Then the man peed on my legs. I couldn’t say anything or run away. Instead, I just turned my face down and cried. I have never forgotten that warm sensation on my legs. When I came back home and told my father what happened on the way, he just listened to me quietly. He was normally a father who would rush to the man’s home and yell, “What on earth did you do to my dear boy!!” I learned then that no matter what we were told or done to, we just had to put up with it, crying inside, and live without thinking about it. That was the attitude we had to live with.

My parents were proud of their home country. I was told to speak Korean at home, but I didn’t like to because I thought I was Japanese, Masaichi Uranaka. Mother always wore chima jeogori, Korean style women’s clothing, although she was told to stop wearing it by our neighborhood association.

In 1939, the Japanese government issued a decree to the Korean people living on the Korean Peninsula and in Japan to change their names to Japanese names in the period between February 11 and August 11 of the following year. My parents were told by someone that people from Gyeongsangnam-do should use the letter 江and those from Gyeongsangbuk-do 山. So, my father changed our family name to 江川 (Egawa). We had used our Japanese name Uranaka (浦中) since the early days of my father’s arrival. I heard that a good friend of my father Mr. Miura (三浦) had named him taking one letter from his last name. My first name was Masaichi (政一), but later I changed the letter to 政市myself. My parents called me Ma-chan.

When I was in upper grades in elementary school, my father made me help him burning charcoal. I had to climb down the steep mountain path with a 15-kg charcoal pack on my back to the road where cars were running. Those packs were really heavy.

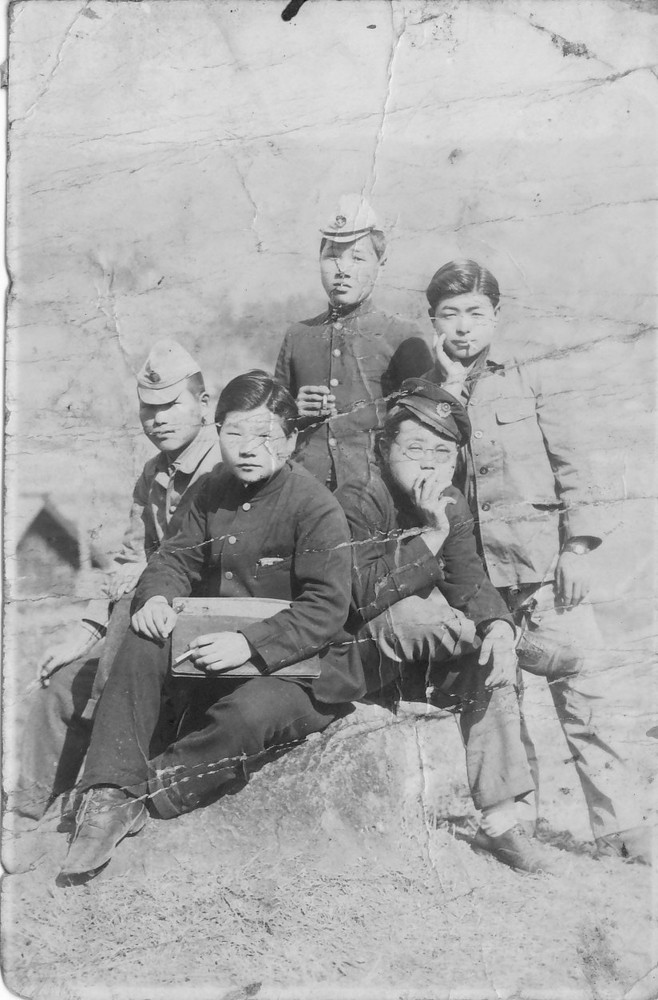

In 1941, when I was a sixth grader, my father was offered a job by the Imperial Rule Assistance Association. The job was to arrange laborers at the construction site of a dock being built by Mitsubishi Shipbuilding Co., Ltd. in Saka-machi (present Saka-machi, Aki-gun, Hiroshima Prefecture), so we moved to a bunkhouse in Saka-machi. We lived in a big makeshift building together with about 20 young Korean men who were brought to Japan. My father arranged the number of laborers and their workplaces every day. I was admitted to Yokohama Higher Elementary School in Saka-machi. Although I was the only Korean at this school, I was not discriminated against.

Higher elementary schools had a two-year course after six years in elementary school. There were few students who continued their education after eight years of those two schools in those days. Most of them got a job or volunteered for the special young soldier system. When I was in the sixth grade, a relative of mine took me to Hiroshima Station. I was so impressed seeing a steam locomotive that I never forgot that awesome sight, so I applied for a job at the engine warehouse of the National Railways. Passing the test to the National Railways, a nation-run company, was thought to be so difficult. On top of that, I was not Japanese, but luckily, I passed. I was extremely happy when I was told my success by my homeroom teacher. After a while, the principal called me to his office and handed me an envelope, saying, “Take this envelope to the engine warehouse tomorrow.”

After coming home, I desperately wanted to see what was inside. I peeled off the seal with the steam of the rice that was on the cooking stove and took out the document inside. Then, the word “Korean” in the remarks column caught my eyes. I wondered, “Why? Why did the principal write this kind of thing? This affects my life! I won’t be employed if they find out I’m Korean.” With that in mind, I single-mindedly erased that part written in sumi ink with an eraser. Now I know that it was illegal to tamper with official papers, but I didn’t even think of that at that time.

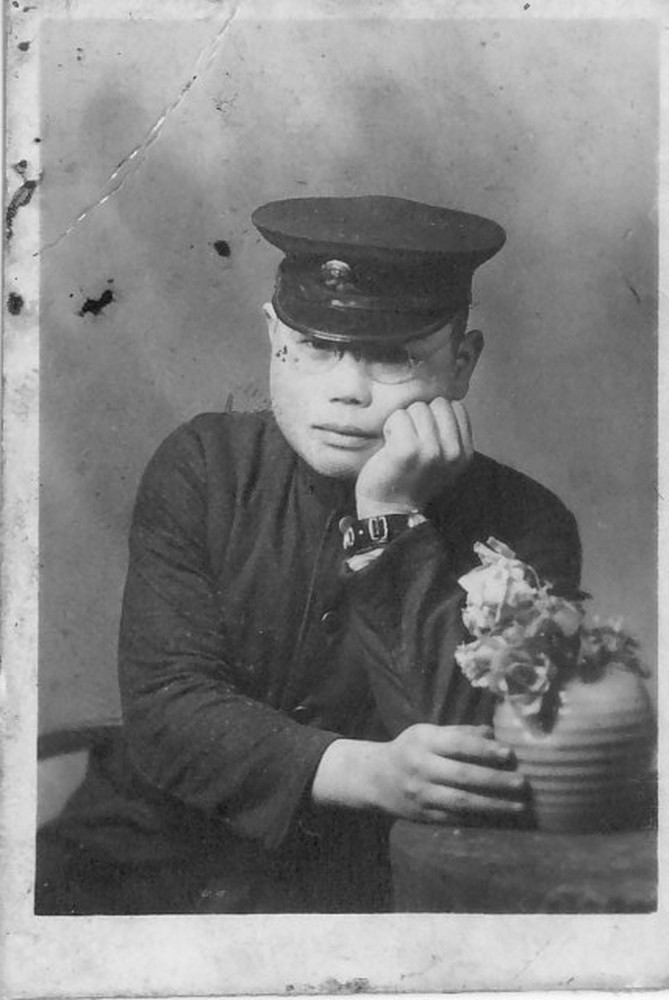

In 1943, when I was 14, I started working for the National Railways without any trouble. I was assigned to the First Engine Warehouse near Hiroshima Station, as I had wished. It was located where Matsuda Stadium is now. Locomotives needed regular replenishment of coal and water at engine warehouses after they ran a certain distance, burning coal. Jobs of new workers like me were cleaning the locomotives coming into the engine warehouse and replenishing the coal and water. Because there was a severe shortage of supplies those days, we didn’t have cloths, so we bundled straw to wipe the soot and clean the locomotives.

I moved into the dormitory when I started working. Life there was exactly like that of a first-year soldier in the military. Older employees woke us newcomers almost every night, made us line up in the hallway and yelled, “Take off your glasses and clench your teeth!” Then, they slapped us on the face, saying, “We are giving you a strong spirit!” Several colleagues who were employed at the same time as me quit in a few months due to the harsh abuse, but I didn’t quit because I liked my job. Their violence continued until I left the dormitory.

To me, the most unendurable thing was meals. For the first few months in the dormitory, meals were a mixture of rice and dhurra sent from Manchuria. However, even dhurra was gradually reduced and the meals became a mixture of rice and soybean dregs. Soybean dregs are made after squeezing the oil from soybeans, and they are now used as animal feed. I couldn’t eat them. I separated out the soybean dregs and just ate rice, only half my meal. It wasn’t enough for a 14-year-old boy with a big appetite, so I was always hungry. I lived in the dormitory for about two years, but I couldn’t stand it anymore. Finally, I decided to commute from my parents’ house. They had moved to Hera, Hatsukaichi at that time. My father had finished his work in Saka-machi, and he was working at a bunkhouse in Hatsukaichi. Since it was a bunkhouse, I didn’t have any complaints about what I ate. From Hatsukaichi, I could take the train to Hiroshima Station, where I worked, without changing trains.