Lee Jong-keun

"Don’t stay silent!"--Raise your voice!

7. Telling my A-bomb experience all over the world on Peace Boat

One day in 2011, I read an advertisement about Peace Boat in the Chugoku Shimbun Newspaper, “Cruise around the world. Free boarding for A-bomb survivors.” I thought, “I wish I could travel around the world for free” and applied without taking it too seriously. I was interviewed by Akira Kawasaki, the Peace Boat director, and talked about my A-bomb experience. I didn’t expect to be chosen since I had never told my story before, but then after a while, I received a notification that I was chosen.

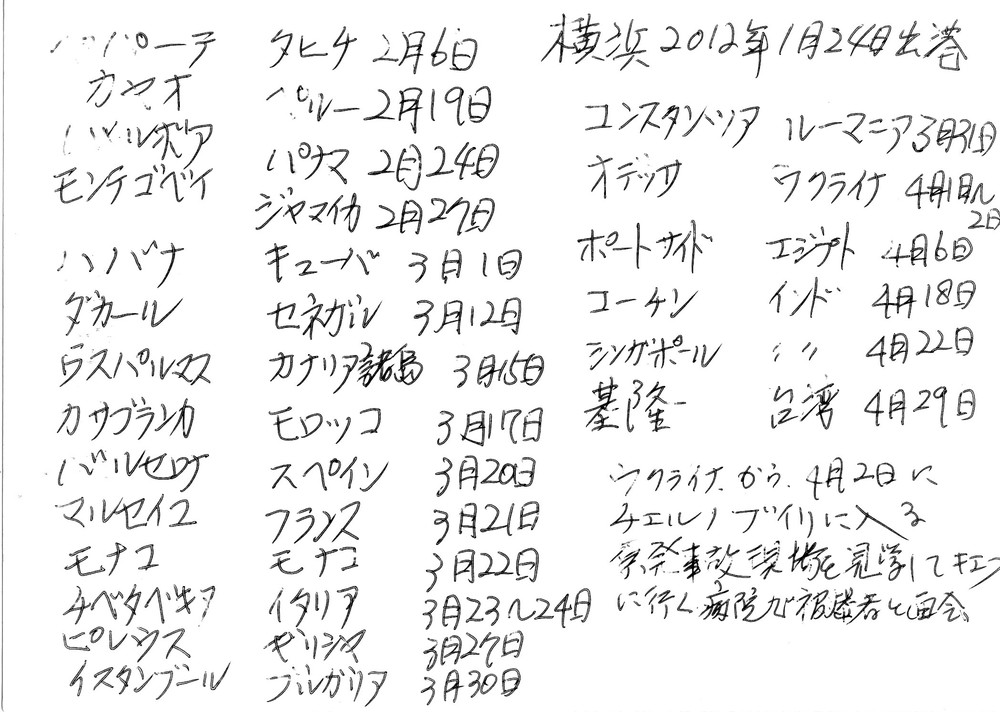

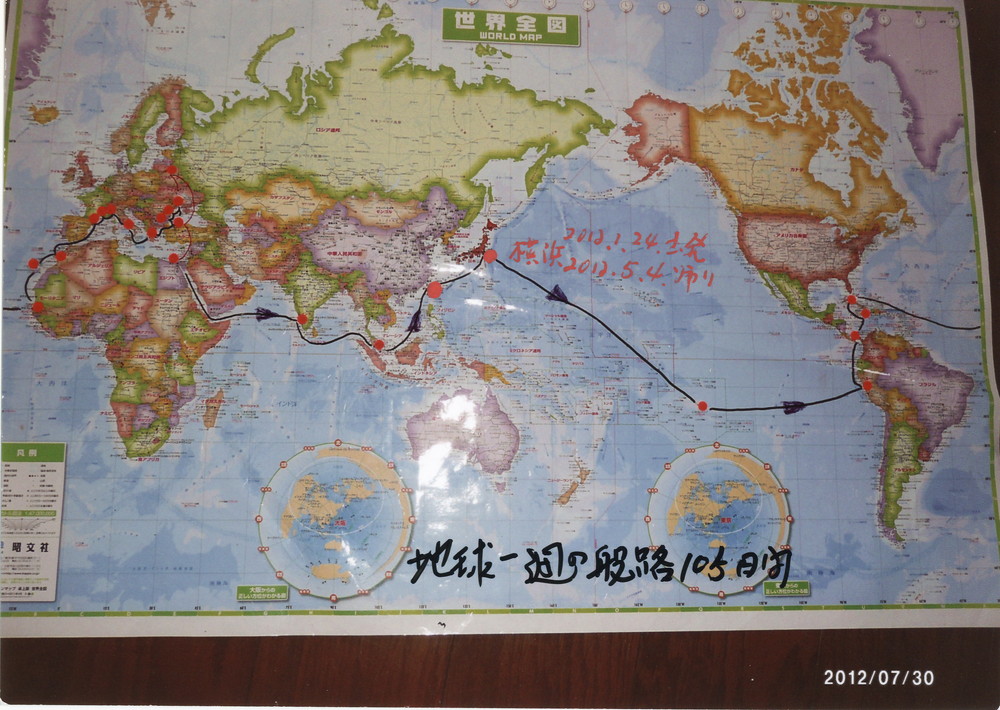

The boat departed from Yokohama Port on January 24, 2012. Five A-bomb survivors from Hiroshima and five from Nagasaki embarked on a voyage of more than 100 days, together with about 1,000 ordinary passengers and crew. I was told to make a speech at the departure. The boat traveled around the globe eastward, stopping at Tahiti, Peru, Panama, Cuba, Senegal, Spain, France, Italy, Greece, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, India and Singapore. The boat called in 22 cities in 21 countries, and A-bomb survivors’ testimonies were given in 12 cities. I was exposed to the bomb at the age of 16 but I only told my experience for the first time at the age of 84.

At each meeting held on board and at each port of call, one of the A-bomb survivors was assigned to tell his story, while the rest of the survivors attended the meetings and listened to their speeches. As a result, we didn’t do much sightseeing. When I listened to other survivors’ testimonies, I was surprised that they also had had maggots on the scars of their burns after the A-bombing. I felt embarrassed that I had maggots on my body, so I had refused to talk about my experience of the A-bombing, even if I was asked. I had thought I was the only one who had maggots on my body, so after that, I added the story of maggots to my speech.

In Cuba, we met with former President Fidel Castro. He was a very friendly person, and when I talked about my A-bomb experience, he told me I should publish a book in Spanish. I was also surprised to see American classic cars such as Fords and Chevrolets running in the streets.

In Senegal, located in western Africa, we visited Gorée Island, the former slave trade hub off the capital Dakar. In the 400 years from the 16th to the 19th centuries, about 15 million young men and women who had lived ordinary lives were suddenly captured and taken to the American continents as slaves. The island was registered as a World Heritage Site in 1978, and the facility where the African people who were captured and housed is now a museum called, “Slave House.” Thinking of its inhumanity, I thought of the Korean people living in Japan. The museum director said, “In terms of inhumanity, both the A-bomb survivors and the enslaved blacks are the same. Why not build a statue of A-bomb survivors next to the black man and woman statue in front of the museum?”

Calling at ports in Spain, France, Greece, etc., we survivors talked about our own experiences in turns. I gradually became accustomed to giving my speech, adding something and removing something each time. All the survivors attended the talks and shared their thoughts with each other at the next day’s meeting. At first, I was only talking about my A-bomb experience, but one day, one of the lecturers, Kwak Kwi-Hoon, a Korean A-bomb survivor, said, “Your story is too light. You should add stories of discrimination against Koreans living in Japan to your speech.” Lecturers were the people who were on board for a short period of time to give speeches to the passengers. Therefore, I added my experience of discrimination in the next speech in Greece. Then, at the meeting the next day, two Japanese people yelled at me with great angry looks, “Don’t tell bad things about Japan!” I couldn’t understand their anger because I only talked about the facts that had actually happened to me. The two even said that they were going to leave the Peace Boat unless I stopped talking about discrimination. However, Mr. Kawasaki, the director of Peace Boat, supported me, saying, “There is nothing wrong with what Mr. Lee said.” Then, they targeted their anger at Mr. Kawasaki and blamed him. The two stayed until the end of the trip without disembarking, but in an awkward atmosphere, they never talked to me.

After that, Mr. Kawasaki and seven A-bomb survivors flew from Egypt to Odessa in Ukraine. We went very close to the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, which caused the worst nuclear accident in history, and visited the town that became a ghost town due to the accident. In Belarus, we exchanged opinions with medical staff, residents, and people involved in the decommissioning work. A person who was working at the building site of the New Safe Confinement, which is planned to confine the remains of the contaminated reactor at Chernobyl, said, “I think it is impossible to contain the radioactivity forever.” People living close to the area asked us about our physical damage from radiation and compensation by the government.

After returning to Japan, Mr. Keisaburo Toyonaga, who had been working for Korean survivors living in Japan, saw the newspaper article about my experience and contacted me. He hadn’t known about me because I had never testified as an A-bomb survivor in Hiroshima before. He asked me to tell my story to school children. As I was reluctant, he said, “Why don’t you just talk about your experience on the Peace Boat?” So, on a very hot day in August in the shade of trees in Peace Park, I told my A-bomb story for the first time in Hiroshima. With that experience, I decided to be a storyteller of the Peace Memorial Museum.

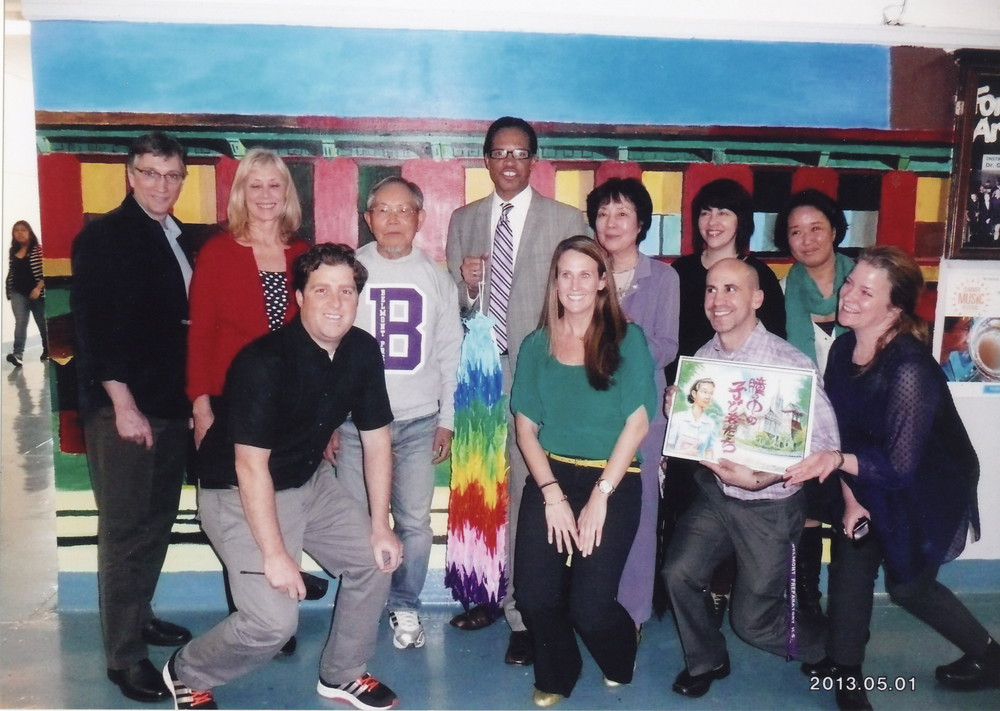

I was invited by Kathryn Sullivan, the director of Hibakusha Stories, an American anti-nuclear organization, who was aboard the Peace Boat as one of the lecturers, to come to New York and tell my story. The following year, 2013, I went to New York and had opportunities to visit several schools and the Japan Society to talk about my A-bomb experiences. I also met Clifton Truman Daniel, grandson of President Truman, who had ordered the dropping of the A-bombs.

The next year, I applied for Peace Boat again and told my story all over the world. As opposed to the previous tour, the boat cruised westward around the earth. This time, the number of A-bomb survivors on board was six from Hiroshima and two from Nagasaki. We visited 20 cities in 18 countries including Singapore, Sri Lanka, Jordan, Montenegro, Spain, Venezuela, Peru, Chile and Hawaii. Our stories were heard in 14 cities in 12 countries. In Venezuela, we met the President, who said, “Human beings should never repeat the tragedy suffered by Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Our visit was broadcast by many media outlets throughout Central and South America. Al Jazeera also came and aired the meeting to Arab countries.

When we visited France and Spain, we had opportunities to talk with anti-nuclear and environmental groups. The T-shirt I was given in France said in Japanese, “Don’t stay silent!” I like the words so much that I sometimes wear it even now.

. Together with some other passengers, I also went to Auschwitz, which was provided as a special program. There, a Japanese named Mr. Nakatani guided us. I couldn’t stop crying in the exhibition building where women’s hair, small children’s shoes, glasses, etc. were piled high in glass cases in each room. Then, we looked around the room where people were made to take showers before they were killed, and the gas chamber where they were actually killed. When Jews and political prisoners from all over Europe arrived at the camp, they were first divided into two groups—those who were able to work and those who were not. About 70-75% were judged to be useless and were taken straight to the shower room. Women were shaved bald. By that time, they must have known that they would be killed. I couldn’t help wondering how they had felt when they were taken from the shower room to the gas chamber, a little farther away. I was exposed to the light of the A-bomb at the foot of Kojin Bridge, but at that time, I didn’t even think that I might die. However, the people who took a shower there knew they would die. It is said that even 90% of the people who had been judged to be useful died due to poor treatment and hard labor. Those who were weak, injured, or sick were sent to the gas chamber. What a terrible thing humans can do!