Park Nam-joo

The A-bombings Should Never Ever Be Repeated

7. Life after that

The wife of our Korean neighbor had a brother who studied at a preparatory school in Tokyo, aiming to attend Waseda University. Since living in Tokyo was so tough, he delivered newspapers and milk every morning. Then, before the Pacific War started, he had to go back to Korea for military service and returned to Japan after serving the Japanese Army in Manchuria. As the Korean peninsula was colonized by Japan then, Korean people in Japan went back and forth to their homeland feeling like it was a domestic trip. Our family, too, visited our grandparents in Korea one summer.

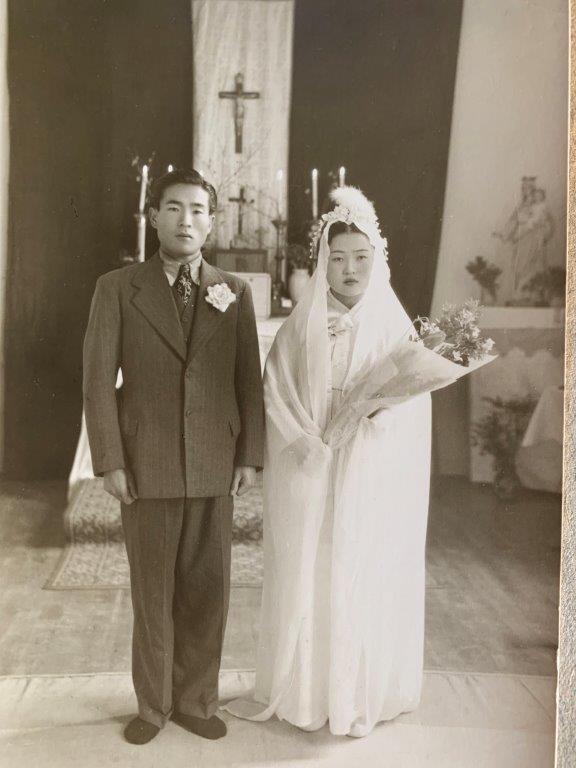

When he heard of the A-bombing, the brother was very worried about his sister and visited her in Hiroshima, riding on the train from Tokyo for two days. Then, after the end of the war, he went back to his hometown in Korea to stay with his parents for a while, but came back to Japan, desperately wanting to continue his education in Tokyo. This time, he had to smuggle himself into Japan, because Korea was not a Japanese colony anymore, and no one could enter without a passport. However, he soon realized that Tokyo was not a good place to study calmly at his own pace, so he moved to Hiroshima, staying with his sister, our neighbor. Then, considering that both our families were from the same village, and his family used to be in the ruling class in Korea, called Yangban, my parents and his parents decided that we should marry. In those days, most marriages were decided by parents, unlike nowadays when people get married loving each other. So, we got married in January in 1949. He was 23 and I was 17.

Life was extremely difficult after we got married. My husband didn’t like to work for other people and never tried to find work. Since we lived close to my parents, I helped my mother make and sell illegal doburoku. At that time, the government hired a lot of unemployed people and had them work at construction sites. There were many workers building the 100-Meter Road, later called Peace Boulevard, near our shack. During lunch break and after work, they would come to buy our doburoku for 10 or 20 yen a cup. Later, the Hiroshima branch of the Korean Residents Union in Japan was established, and my husband got a job as a Korean language teacher there, where he earned 15,000 yen a month.

The following year, twins were born to us prematurely; however, they died one after another soon after being born. I heard about a lot of stillbirths and premature births in those days, especially, for the first babies. When our first baby died, three people in white from the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) came to our door. They were carrying a white box, which looked exactly like a coffin for a baby. We never informed our baby’s death to them, but there might be a rule that midwives had to report deaths to the ABCC. They said, “Would you kindly hand your baby to us? We will bury the body with special care. We’ll give it back to you later if you would like us to.” Hearing their words, my husband got red with anger and firmly refused. Many people around us gave their babies to them, hearing that their bodies would be buried in proper way, since their family temples had been destroyed, and their family graves had collapsed in the A-bombing. But since both of us were Catholic, we held our babies’ funerals in our church and had them buried in its cemetery.

After that, we were blessed with three girls and a boy. When our eldest daughter turned two years old, the staff from ABCC came to our shack in a jeep to have her tested there. I dressed her with new underwear and clothes and went there with her. When we left the exam, they gave her some biscuits, but we never received the test results. We realized that they were just collecting data and felt exploited. After that, we refused to have our children tested.

Five or six years after our marriage, using the money saved by collecting iron scrap and selling doburoku, I started a new business of pig farming. My husband wasn’t interested in this sort of business. Beginning with two pigs, I bred and sold pigs in the open space which had been created to make a fire lane during the war, now Peace Boulevard. I fed them sake lees, residual dead yeast, which was a by-product of making doburoku. Several years later, due to the construction of Peace Boulevard, we had to vacate our shack and the space I used for pig farming. We moved to a nearby public apartment in the same neighborhood, and I kept about ten pigs there. In 1964, with the compensation money for our removal and our savings, I bought a large property of 400 tsubo (about 1300 square meters) in Furuichi (present Asa-minami ku, Hiroshima). The following year, I built a modern Danish-style concrete pigpen and started large-scale farming with 400-500 pigs. To ensure pigs’ food, I made a contract with the meals supply center of Toyo Industry Company to buy their leftover waste and bought a two-ton truck to carry it back. It was especially hard for me to sort plastic materials out of the leftovers I received.

The business was going well, but about 20 years later, a strong typhoon hit Hiroshima. The nearby Furukawa River flooded, and the pigpen and most of the pigs washed away. The government decided to buy the land for a flood control project, and I had to vacate the land again. This time, I was given more than 120 million yen for the cost for removal and compensation for my business. My tax accountant advised that rather than saving the money in the bank, I should use that money for starting a new business, which would avoid a lot of tax. Consulting my husband, I decided to buy some land and build apartments for rent. I was old enough and did not want to do hard labor anymore. I wanted to lead a calm life without worrying about money. It was in the middle of the bubble economy. Banks were eagerly seeking clients who wanted to borrow money. So, I borrowed a lot of money from the bank and bought a large piece of land, the price of which was far higher than what I had. Unfortunately, the bubble suddenly burst, and instead of building apartments, I had to sell my land to pay off my debt. The bank that had desperately wanted to lend me money suddenly changed its attitude and would not lend me more money to build an apartment building. Instead, they pressed for repayment of the original loan. The price of the land fell drastically from the purchase price when I sold it, and I ended up losing all the money I had received from my pig business.

Lower left my mother, right her sister-in-law

Taken in Korea after the normalization of diplomatic relations in 1965