Keisaburo Toyonaga

My Life Dedicated to A-bomb Survivors Overseas

- 1. My Background

- 2. My August 6

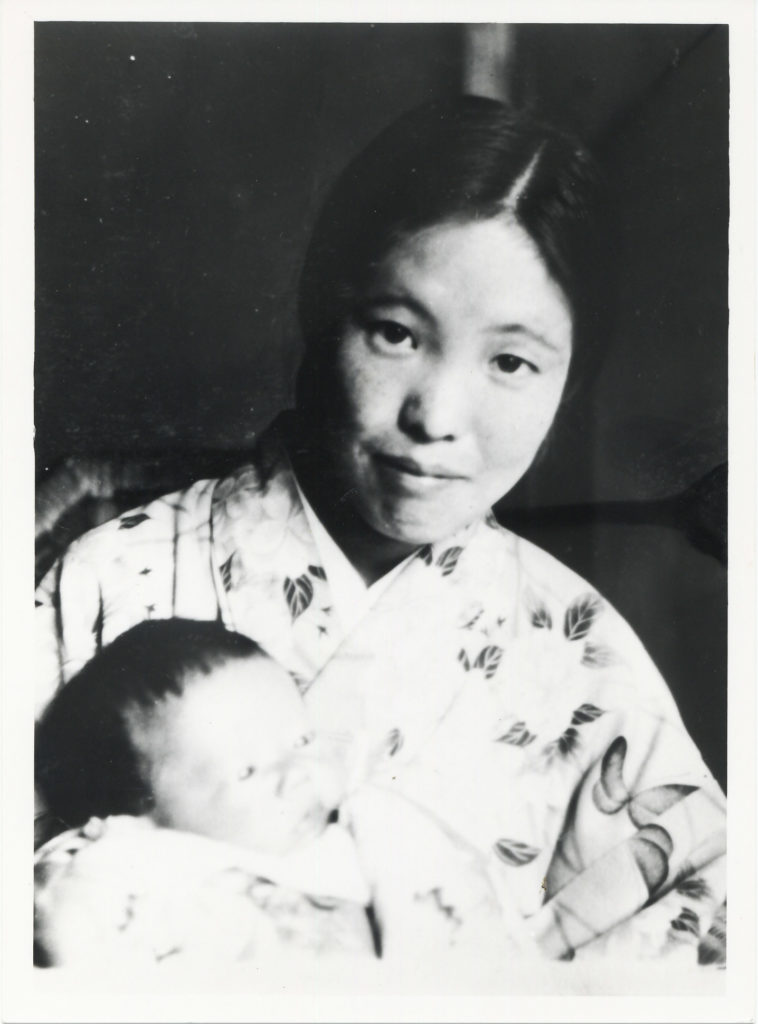

- 3. My Mother and Brother on August 6

- 4. After August 7th

- 5. Life after the A-bombing

- 6. Some children could not use their real names.

- 7. I Want to Support the Forgotten A-bomb Survivors Living Abroad

- 8. “A-bomb Survivors Are A-bomb Survivors Wherever They Are!”

- 9. Beginning to Give My A-bomb Testimony to Students Who Visit Hiroshima on a School Trip

- 10. Passing the Peace Baton to Young People

1. My Background

I was born in 1936, as the first child of Taichi and Tsuyako Toyonaga in Yokohama. Although both of my parents were from Hiroshima, we lived in Yokohama then because my father was a police officer assigned to work as a guard at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. When my mother was about to give birth to me, he couldn’t come home because the February 26 Incident (an attempted military coup) had taken place just a month before, so my mother gave birth to me by herself. When I was three years old, my father suddenly decided to go back to his hometown, Hiroshima, so I don’t have any memories of Yokohama.

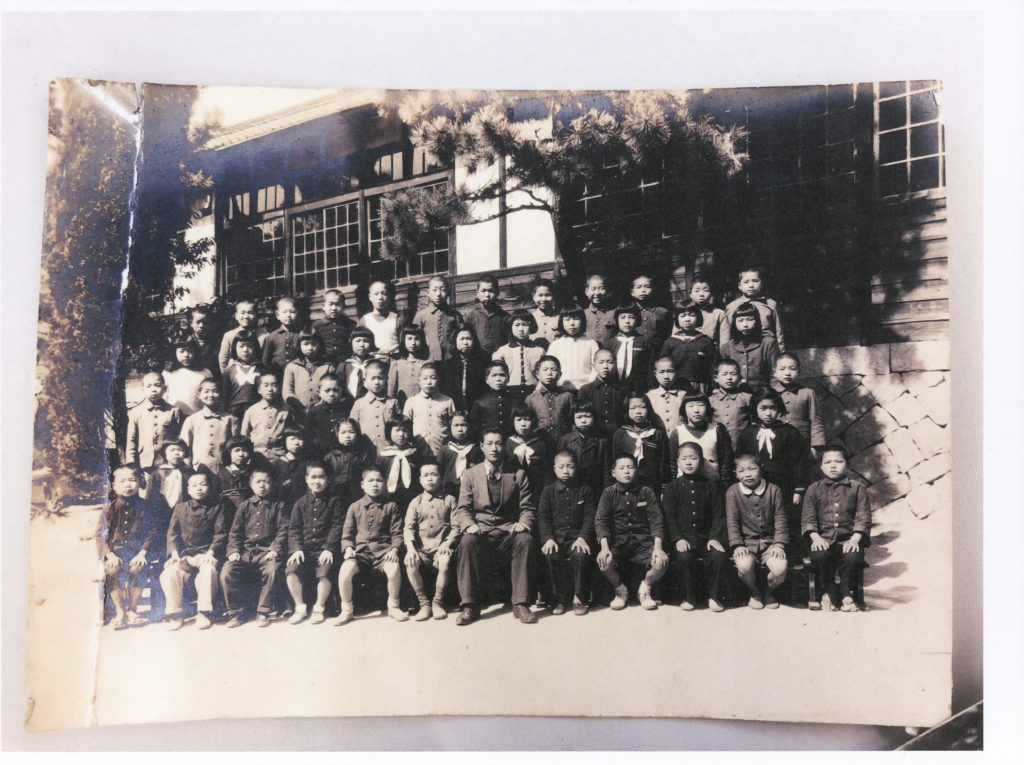

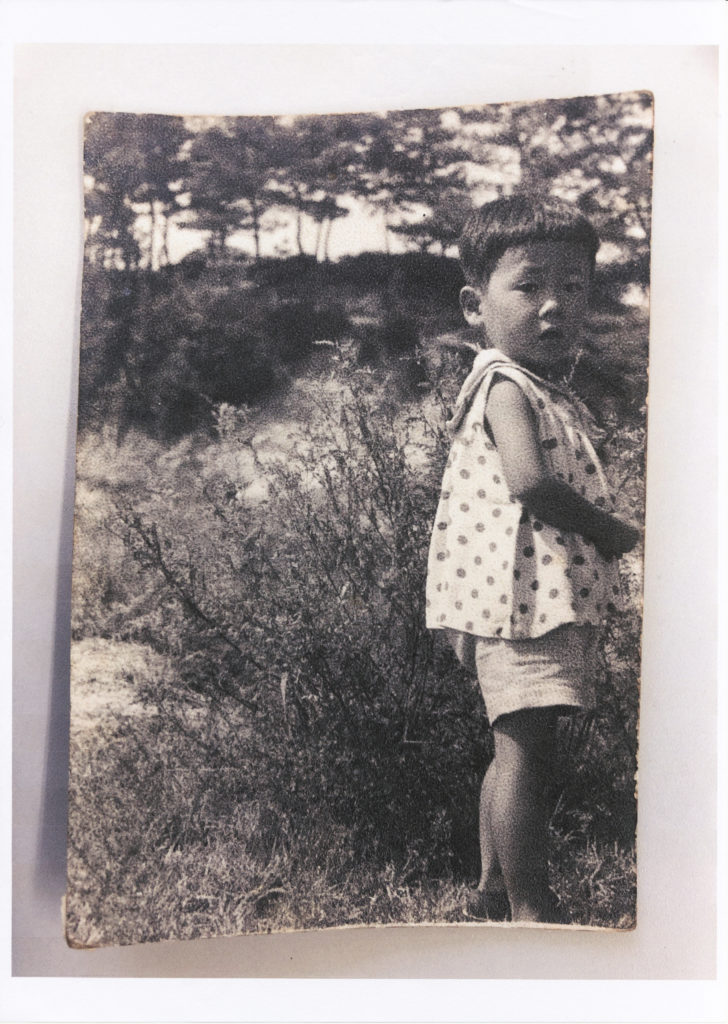

In Hiroshima, we lived in Onaga-cho (present Yamane-cho, Higashi-ku, 2.5km from the hypocenter.) In 1942, my brother, Hiroyuki, was born, six years younger than me. When Hiroyuki was just one year old, my father died. He was just 41. Although we lost our family provider, he left some money for us to live on, and we kept a life of relative comfort. I went to Hiroshima Jogakuin Kindergarten, although it was not common in those days for small children to go to kindergarten. Then, instead of nearby Onaga National School near my house, I entered Noborimachi National School, out of my school district, because many of my friends went there. However, about a year later, I was told to transfer to the school near my house. I suppose children had to go to neighborhood schools because of the danger caused by air raids in the city. In the new school, I felt lonely without any friends there.

In 1945, as the war situation deteriorated, more and more cities in Japan’s mainland experienced air raids, so children from the third through sixth grades in urban areas were evacuated to rural areas. Children who had relatives in the countryside were sent to them, and children who didn’t have relatives were evacuated to temples and other facilities under their teachers’ charge. Being a third grader, I was sent to my late-father’s parents’ house in Fuchu-cho, Aki-gun (5km from the hypocenter). At Fuchu National School, I was a newcomer with no friends, and there were no children to play with in the neighborhood. Feeling very lonely, I moved back home, and after that, I walked all the way from Onaga-cho to school in Fuchu-cho every day. It took me about an hour.

However, back in Onaga-cho, all my friends had gone to evacuation places. Only first and second graders remained, so I had no choice but to play by myself with a kendama or throw a ball against the wall in the East Military Drill Grounds nearby. Kendama is said to be originated in Hiroshima and was called a “sun-moon ball” back then. I remember the song we sang playing with the kendama: It is fun playing with Hiroshima’s popular sun-moon ball. I remember the different system of janken game, or scissors-paper-rock game, in which you had to lose to win. It was played among boys, and we called different words for it. We called wan kou nou kou hoi for that different system janken game, but the meaning of that call is unknown.

Honestly, I had no pleasant memories of my school days. On arriving at school every morning, we had to bow to the Hoanden (a shrine-like building for housing photographs of the Emperor and Empress and a copy of the Imperial Rescript on Education). Teachers had absolute power, and in classes we had to sing military songs. They taught us about Western brutality and told us how noble the Special Attack (Kamikaze) Corps were. So almost all of us boys dreamed of being kamikaze pilots. I didn’t have such dreams because I knew that I wouldn’t be qualified because of my weak constitution.