Kiyomi Kono

1. My Background

I was born on March 11, 1931, in a farming village in Ichikawa-mura, Takata County (present Shiraki, Asakita-ku, Hiroshima, approximately 35km from the hypocenter). My father, Kaneo and my mother, Tama, had five children. I was the fourth. My eldest brother, Toshikatsu, was their first child and 12 years older than me. My eldest sister, Sumiko was nine years older, my elder sister, Midori, five years older, and my younger brother, Kazuhiko, three years younger. When I was born, my father got in a bad mood, because he had three girls in succession. In those days, people were proud and happy when they had boys born in their families. He went out of the house without saying anything and didn’t even give me a name. So I was named by my mother and my father’s brother in place of him.

My father was a village councilor and the headman of our neighborhood association. I remember my little embarrassment when I saw my father among guests attending my school’s entrance and graduation ceremonies. Although our family business was farming, he was too busy in taking care of the village and our neighborhood to do farming. So, my mother was doing the farm work such as growing rice and vegetables along with housework and childcare. As we were a relatively big farming family, we didn’t have to worry about food even during wartime. However, we had to eat rice porridge or rice cooked with barley or diced potatoes, not simply cooked white rice, because much of our rice crop was delivered to the government. In our neighborhood, there was a barber. He was drafted into the army, leaving his wife and two little children with no income. His wife died of starvation later leaving two little children.

My mother never got angry. She scolded us using proverbs whenever we were mischievous. One day, I took a 50-sen coin (old coinage before being unified to yen) left on my father’s desk without permission and bought candies at a nearby candy store. When my mother knew that, she told me a proverb, “The day has eyes, the night has ears,” which means that God in the heaven, God on the earth, your conscience, and you know, however hard you keep your deed secret. “Don’t speak evil of anyone” and “Don’t make any remarks without thought.” were among my mother’s other sayings.

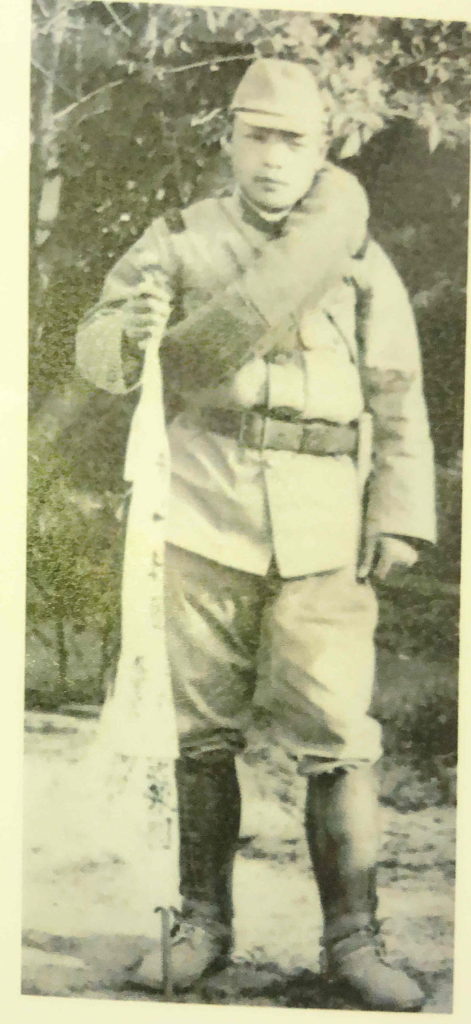

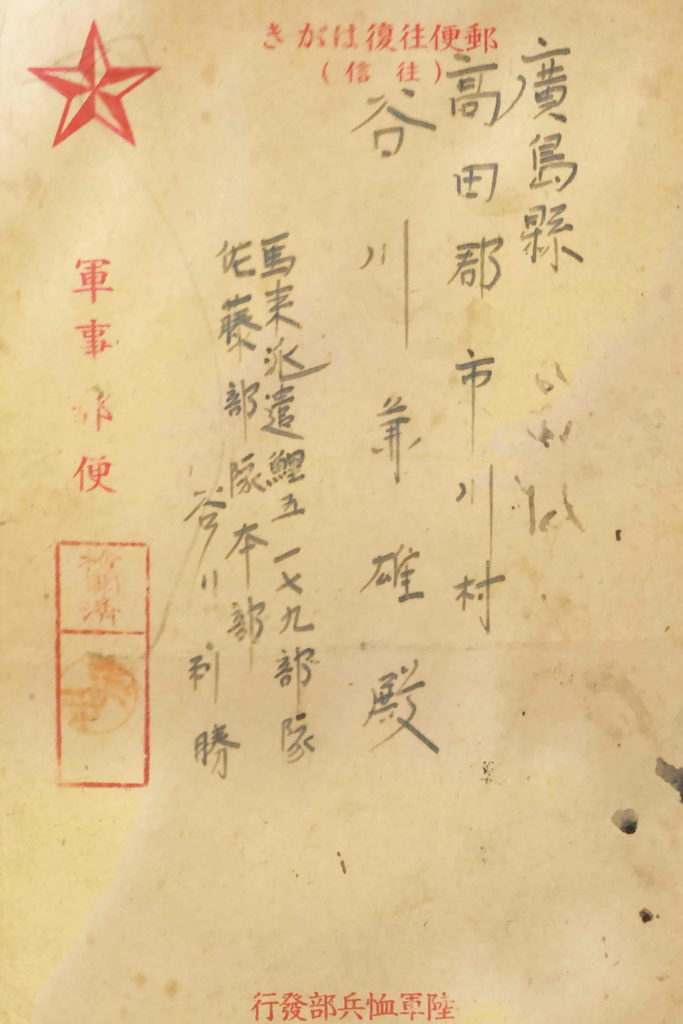

My brother, Toshikatsu, graduated from Takata Middle School and got a job at the Kure Naval Arsenal, the naval shipyard where the Battleship Yamato was constructed. But one year later, he volunteered to be a career soldier. In my village, all the people saw a soldier off heading for the warfront at the railway station after we paid a visit to our local shrine to pray for his long-lasting good fortune in battle. I remember the day when Toshikatsu left for the front. I was a first-year elementary student. It was a very cold day with snow on the ground up to our knees. Those days, elementary students were collected to line up in front of the station and waved small rising-sun flags every time soldiers left for the front. When soldiers returned dead from the battlefield, we lined up the same way, but with no national flags in our hands. I remember a sad-faced young widow standing with an unvarnished wooden box held to her chest, which contained her dead husband’s ashes. We were told that we shouldn’t cry or shed tears for the dead soldiers because dying in battle was considered an honor.

Every day at school, we had a morning assembly, where our principal loudly chanted a gyosei (a 31-syllable Japanese poem by Emperor) and students followed him in a chorus. In moral training class, we learned the Imperial Rescript on Education by heart. I can recite it from memory even now. We had different ceremonies relating to the Emperor, such as the Emperor’s Birthday and Empire Day, the date the first Emperor Jimmu was enthroned. I faithfully believed that I would die for the Emperor, and that I was willing to give my life to him. I was sure that every student believed the same thing. Small children are too pure and innocent to doubt what teachers say. Education is such a dangerous thing.

I liked reading books, but unfortunately there weren’t any books for us at school. My father bought me fairy tales, but I had read them already. The family next door had moved to Manchuria leaving their house as it was, leaving books on the bookshelves upstairs. I often entered into the house and read them there without permission. Those books ranged from the ones for young children, such as A Little Princess, Little Lord Fauntleroy and Peter Pan, to others difficult for elementary students. I read them one after another. I even read books for grown-ups, such as books by Masao Kume, Koroku Sato and Kan Kikuchi.

In 1943, I graduated from Ichikawa Elementary School (Ichikawa National School, then) and entered Mukaibara Girls’ Secondary School. In secondary school, girls received much more militaristic education than in the elementary school. Every day, at the morning assembly, we practiced fighting with bamboo spears. It seems absurd now, but we were in deadly earnest back then. The enemy would have shot us to death before we stabbed them. A retired army officer, called a training officer, came to our school once a month and gave us military training where we recited the Imperial Rescript to Soldiers in chorus. In boys’ middle school and above, military training by commissioned military officers assigned to each school was a required subject.

The war situation was getting worse. Under the National General Mobilization Law enacted in 1938, secondary school students in urban areas were mobilized for building demolition or to factories. Even girls in rural farming villages like me had to work. The third-year and above girls in our school were sent to the Kure Navy Arsenal. Our school was converted to a branch factory of the Army Clothing Depot, and the first-year and the second-year girls did sewing at school every day. Many sewing machines were lined up in classrooms and the auditorium. Each of those machines had its owner’s name and address written on its leg. I thought those owners were probably ordered to deliver them to the government. Every address was in Hiroshima City because there were no sewing machine owners in rural villages back then. Every day we made soldiers’ underwear using those sewing machines. The cloth was cut in advance to be ready for us to sew. Girls were divided and assigned to each part to work efficiently on a line, such as creasing the cloth to sew easily, ironing the creased cloth and sewing it.