Kiyomi Kono

I can’t forget, and we must never forget.

3. August 7

In the morning, Mrs. Shimogishi, who lived near my house, her son, my mother and I got on the first train bound for Hiroshima. Mrs. Shimogishi’s sister was living in Ote-machi, in the center of Hiroshima. Her son was a student at Hiroshima Municipal Technical School, and he accompanied us because he had the knowledge of the location. Actually, thanks to him, we could walk around there without getting lost.

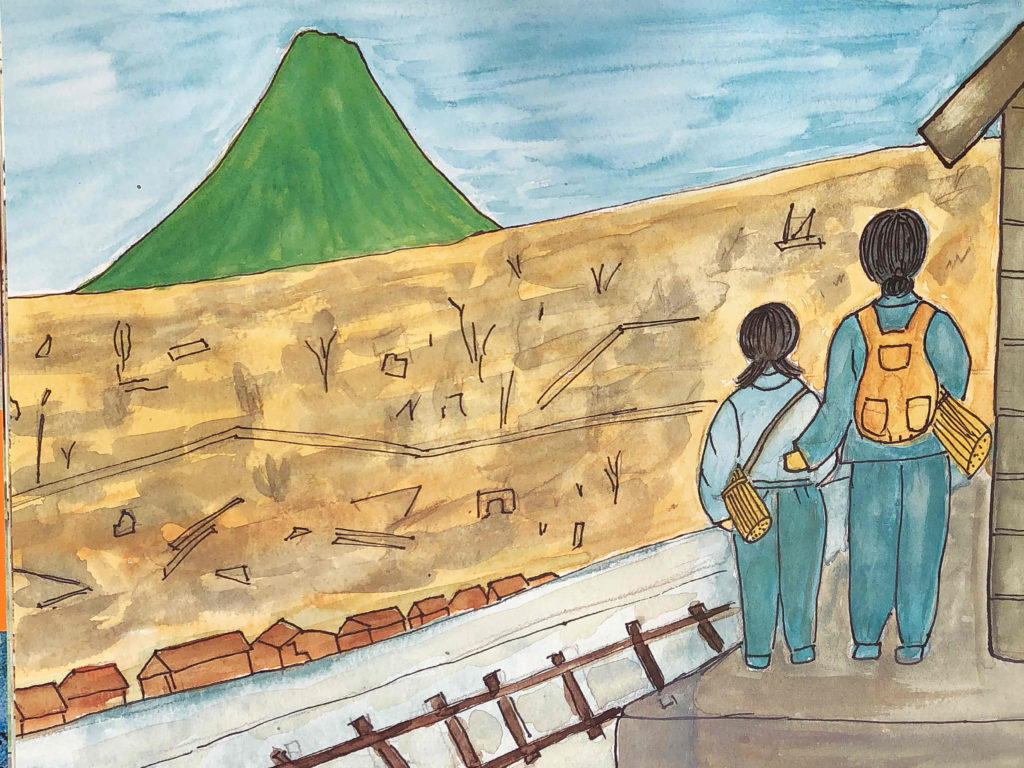

The train we took had six or seven cars, which were filled with people who were going to Hiroshima to look for their families or their friends. Everyone wore brown tunic-style clothes. The train ran slowly, stopped often along the way and arrived at Yaga Station two hours later, taking twice as much time as usual. All the passengers had to get off there as the train could not go further. Stepping onto the platform, I almost choked from the stench there. To my surprise, I could see Hiroshima as I had never seen it from Yaga Station. The whole city was a completely black burned field with smoldering smoke here and there. Over the burned-field, I could see green Ninoshima Island. From there all the passengers had to go on foot into the city center.

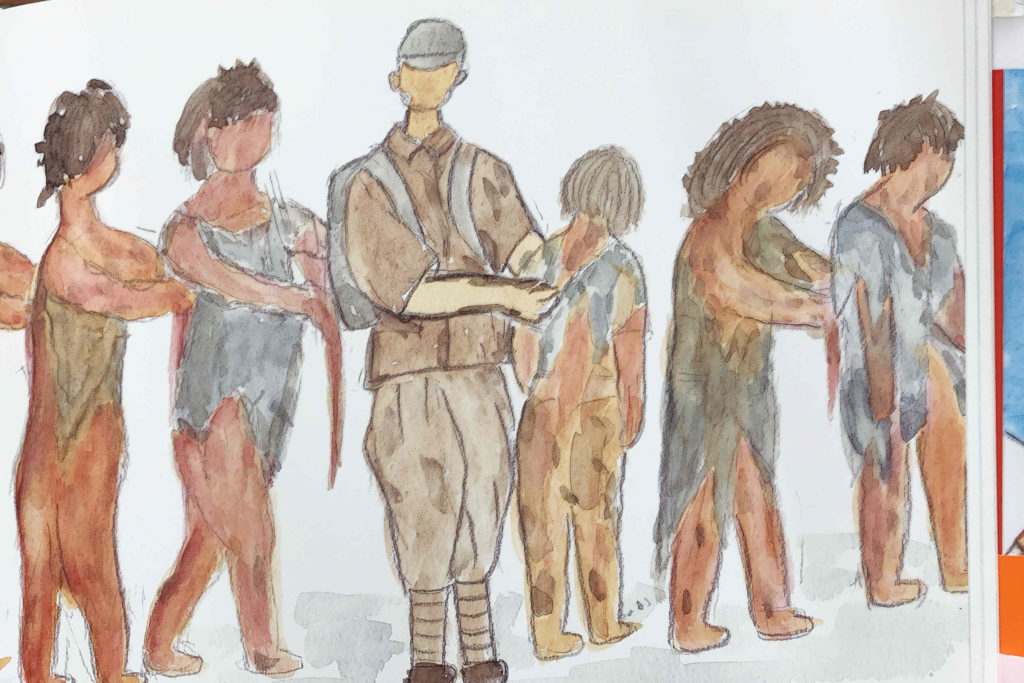

The road from Yaga Station to the city center was flooded with so many people that some people behind us shouted, “Go faster!” and pushed us. On the other side of the road, I saw a long line of people walking in the opposite direction from us. They didn’t look human, with their hair hanging in wild locks, their arms held out in front of their chests, and their torn arm skin sagging from the tips of fingers. They were like ghosts rising up and out of the city. I was so scared that I kept walking without looking at them.

After a long walk, we reached the city center. Many bodies lay like logs on the debris in narrow streets. The bodies, burned by the heat rays and swollen two or three times larger than normal, looked like red demons. We couldn’t recognize whether they were men or women. Jelly-like eyeballs dribbled from the eye-sockets from some bodies. Internal organs, flowing from open wounds on their bodies, turned yellow like an omelet. Some dead people were stretching out their arms and legs into the air. They seemed to try to grasp at something. I saw a burned tongue sticking out from a mouth, which was triangle. Some bodies were like charcoal sticks. I walked down the street, holding fast to my mother in horror, for I might carelessly step on dead bodies. My toes still remember the feeling of something fleshy when I stumbled on the bodies.

Crossing the Hijiyama Bridge, we headed for Ote-machi. On both sides of the bridge, many dead bodies, pulled out of the river, were laid side by side, covered with straw mats. Under one of the mats, I heard a woman’s feeble voice. “Help me. Soldiers, please give me some water! Water! Water! Please give me some water to drink! Anyone!” However, we didn’t do anything, but just passed by her. At that time, we were told that if people with burns drank water, they would die.

The house of Mrs. Shimogishi’s sister was completely destroyed to debris, and we could see smoke rising from the place which seemed to be the kitchen. Leaving her and her son, my mother and I headed for the Red Cross Hospital in Senda-machi, where my sister, Midori, was working as a nurse. Stepping into the hospital, we saw a large number of wounded people filling the concrete floors. They were crying, “It hurts!” “Help me!” “Doctors, hurry!” “Mother, I hurt!” Their voices were echoing on the concrete walls and ceilings. I thought this would be a death cry. I can never forget those voices and the stench still now.

My mother found a nurse there and asked her about my sister. She happened to know my sister well, and she told us that Midori was carried to Ninoshima Island. According to her, ten days before the A-bombing, dysentery had spread in the hospital, and Midori had developed it and had been placed in an isolation ward. The building of the ward collapsed in the A-bombing and my sister was trapped under the building. Luckily, she was pulled out of the debris by soldiers who were hospitalized at that time. Anyway, we were relieved to confirm my sister’s safety.

Midori explained to us later that she had been on the bed by the window and had been narrowly rescued before the fire spread to the rubble. However, two other nurses by the corridor in the same room couldn’t be rescued in time. The isolation ward was completely burned down just after Midori was helped out, so the two might have been burned alive. Midori fled to Sumiko’s house in Ujina, wearing only her summer kimono. As she was barefoot, she put on geta, wooden sandals, around Yamanaka Girls School. Then, she was picked up by a truck of the Akatsuki Corps, the Army Marine Transport, and was taken to Ninoshima Island with other wounded people.

Though it escaped collapse, the reinforced concrete main building of the Red Cross Hospital, located 1.5km from the hypocenter, was heavily damaged, but the wooden isolation ward was burned down. Sixty-nine people, including doctors, nurses, staff and five patients died. Just after the A-bomb was dropped, many injured people came to this hospital seeking help, and more than 30,000 people were treated there in 22 days. (Iwanani Shoten, A-bomb Drawings by Survivors)

Outside the building, I found the dead bodies of middle school boys neatly laid radially in the circular flowerbed. They looked innocent, wearing national uniforms and puttees over their legs. Seeing them, I was strongly moved, because they seemed almost the same age as me. I learned later that they were first-year students of Hiroshima Second Prefectural Middle School. They had been mobilized for demolishing houses and had been lining up for the morning assembly on the bank of the Honkawa River, to the west of what is now Peace Park. During wartime, people demolished houses or buildings to make firebreaks to prevent the spread of fire when air-raided or to protect important facilities from fire. I heard that the students had been cremated behind the hospital the night of the same day I saw them, without their families’ attendance. 344 students and eight teachers of their school died from the A-bombing.

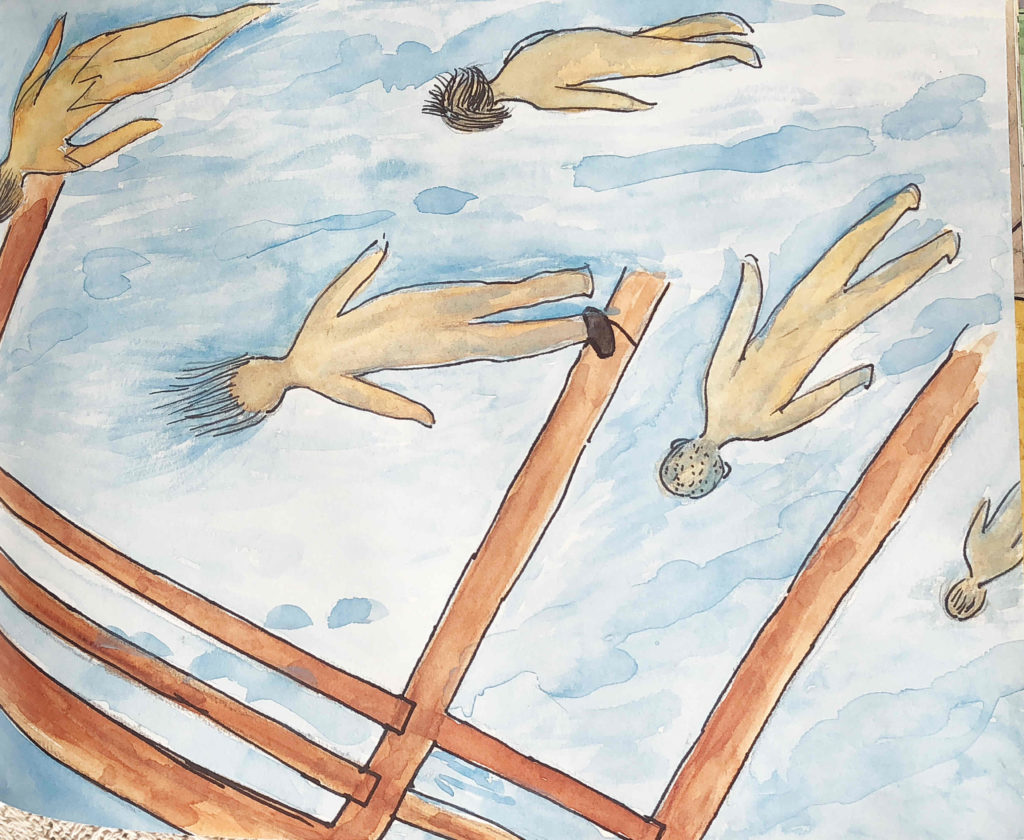

Leaving the Red Cross Hospital, we crossed Miyuki Bridge and headed for the house of my sister, Sumiko, who lived in Ujina. From the bridge, a lot of people were looking down at the river. The rails of the bridge had been blown away by the blast. We saw countless bodies here and there floating in the Kyobashi River, which runs under the bridge, without flowing away. They were almost naked. Some were floating on their sides, others on their stomachs. Someone’s long hair spread around her face in the water. A body swaying in the water was caught by the ankle wearing jikatabi shoes, in the bridge foundation. I don’t know why, but all of them looked white. The west side of Miyuki Bridge was a burned and black field. On the contrary, on the east side, the houses seemed to escape the fires, though they were partially destroyed— houses were slanted, windows broken and roofs fallen. Surprisingly, the scenery was completely different across the river.

We walked to the south along the road where the Hiroshima Electric Railway Ujina Line was running. Sumiko’s house was located past the Kanda Shrine in Ujina, about 4km from the hypocenter. Her house was tilted and the roof and windows were broken, but her family could still live in it. We found Sumiko safe in the house. Finding her safe, my mother shed tears of joy, saying, “Sumiko, you are alive! How wonderful!” However, Sumiko’s husband, who worked for Hiroshima Electric Railway, was buried under a building at work and seriously injured. Her husband’s brother, a middle school student, had been exposed to the A-bombing at his mobilization site and was severely burned all over his body. Sumiko was picking up maggots infesting his wounds one by one with chopsticks. We couldn’t stay long in her house, so we left one hour later to return home the same way we had come.

We crossed Miyuki Bridge again and walked along the streetcar lane. On the road, I saw bodies of humans and horses lying like logs. Soldiers of the Akatsuki Corps collected dead bodies and piled up them like lumber on vacant space. After every 20 to 30 bodies were piled, they poured oil on them and burned them to ashes. Seeing that scene, my mother murmured to herself over and over, “What a shame! I feel terribly sorry for them.” Approaching the city center, we saw some burned and black streetcars off the track. When I happened to look into one streetcar near Kamiyacho, I saw several pitch-black charcoal arms hanging on to straps. Seeing this knocked the breath out of me. A dead horse was lying near Shirakami Shrine, whose body swelled about twice its size.

Some decades after the A-bombing, I got a call from a man who had seen my picture of that streetcar. He said, “I also saw the same black charcoal arms hanging on to straps. Many skulls on the floor were pink and shining.” However, although I saw the hanging arms through the windows, I didn’t see any skulls on the floor. I learned later that 23 streetcars burned on that day. I don’t know whether we saw the same streetcar.

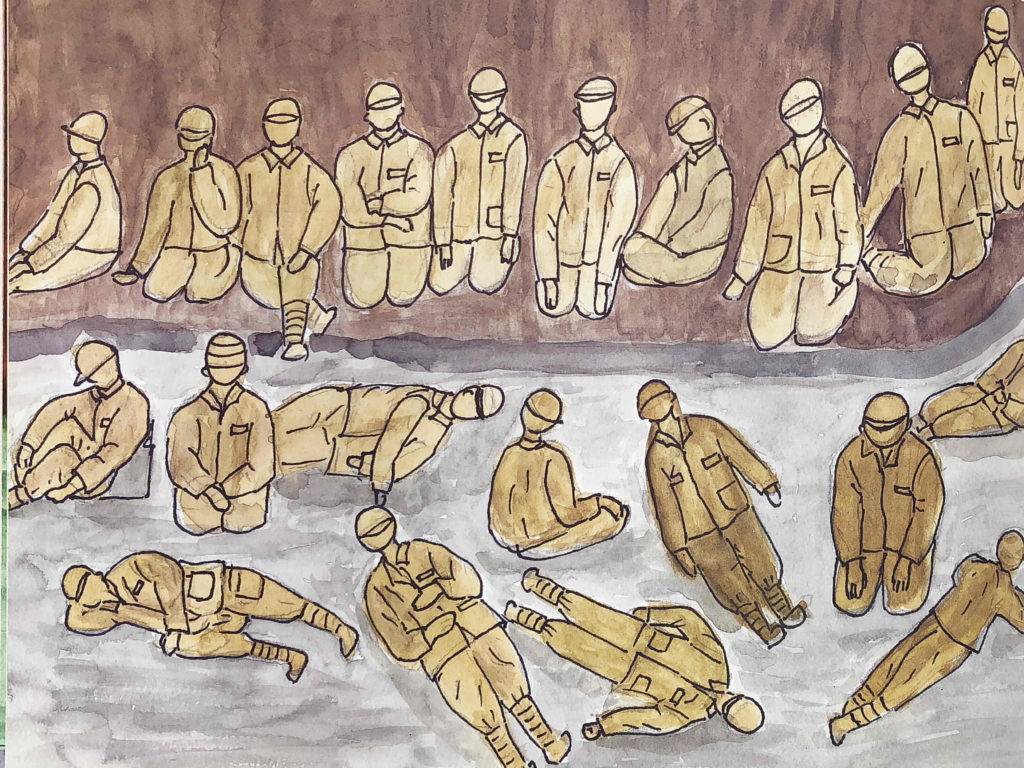

Whenever I saw such cruel scenes that morning, I cried, but in the afternoon, I didn’t feel any emotion and I didn’t cry, either. We finally got to Fukuya Department Store, but the building was burned black inside and only the outer walls remained. On the streets around the building, many dead bodies were laid side by side in rows. Near the department store, 50 to 60 soldiers were squatting down. Though they were not injured, they looked like they were dying, with their faces deathly pale. I happened to meet one soldier’s gaze. I can never forget his eyes that tried to say something to me. For a long time, I was wondering why those soldiers around the department store were dead although they had no wounds or burns. Only later, I understood the cause of their death was exposure to radiation.

From there, I have no memory of how I walked to Yaga Station and how I got on the train to return home. Even now, my memory of that time is completely gone. My mother and I walked around the city center of Hiroshima all day, not realizing that residual radiation remained around there.