Kiyomi Kono

I can’t forget, and we must never forget.

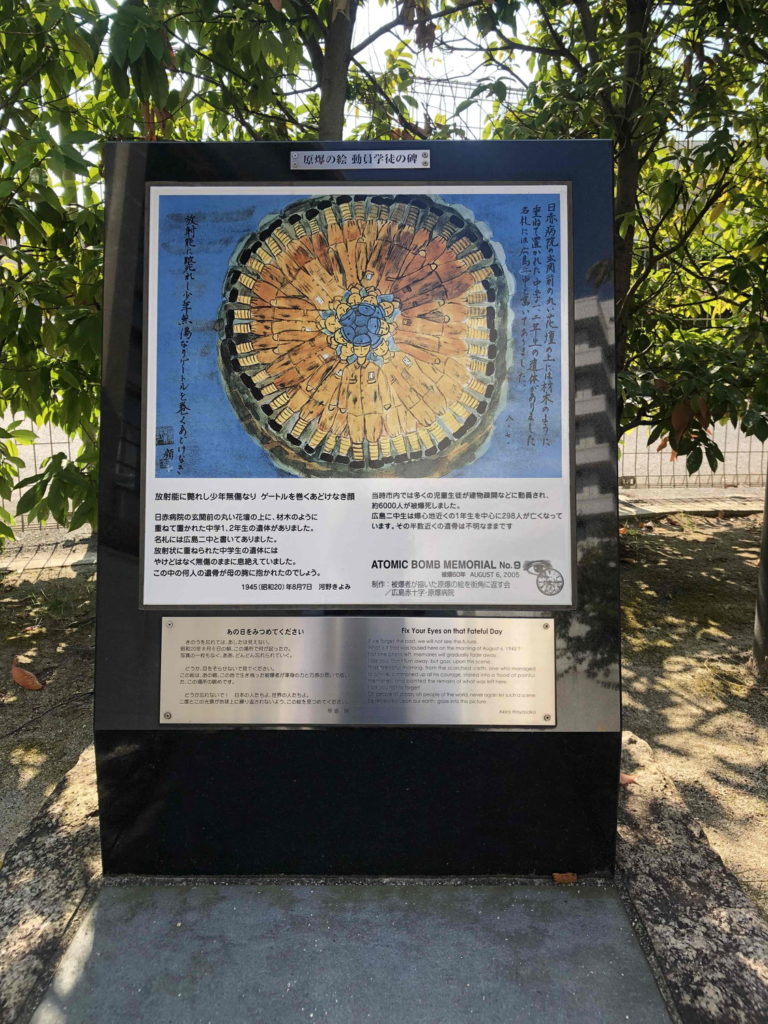

8. Drawing the Students of Hiroshima Second Prefectural Middle School.

In 2003, when I was 71 years old, Hiroshima City, Hiroshima NHK Broadcasting Station and the Chugoku Shimbun Newspaper jointly solicited “A-Bomb Drawings by Survivors.” This was the second time, following the 1974-1975 solicitation done by Hiroshima NHK Broadcasting Station. On the night the news was announced, the students of the Hiroshima Second Prefectural Middle School that I had seen when my mother and I went to the Red Cross Hospital to look for my sister appeared in my dream. I felt as though they were saying to me, “Remember who we are. Please draw us.” I felt that they would be forgotten by everyone if I did not draw them and was motivated by the thought that I must leave something about them behind.

The next morning, I searched my son’s room, who was already living on his own, and found dried-out paints. I had never learned to paint before. First, I recited a sutra in front of the Buddhist altar and prayed, “I will draw those children who passed away without anyone knowing about it.” Then I began to draw. As I painted each of them, the image of how they were, which I thought I had forgotten, clearly came back to me. They all wore the same brown national uniforms and gaiters around their legs. There were name tags sewn onto their uniforms. In truth, their clothes were tattered and their faces were dirty, but I painted their faces as peaceful as Kannon, the Goddess of Mercy, and their clothes clean. It was as if the souls of the children of the Hiroshima Second Prefectural Middle School had moved my hand to paint this picture. I painted this picture only with the thought of wanting to leave behind the memory of these children, who were cremated that night in back of the Red Cross Hospital, without their parents coming to look for them and taking them home.

This painting caught the eye of a screenwriter, Akira Hayasaka, who in 2002, had founded the “Group to Return to the Streets: A-Bomb Drawings by Survivors.” The group selected more than a dozen drawings of the atomic bombing from among some 3,600 drawings by survivors in response to the two calls from NHK. They were then made into ceramic boards and installed at the locations depicted in the drawings. My drawing was installed next to the entrance of the Red Cross Hospital, as the ninth drawing to be unveiled on August 6, 2005. I also attended the unveiling ceremony.

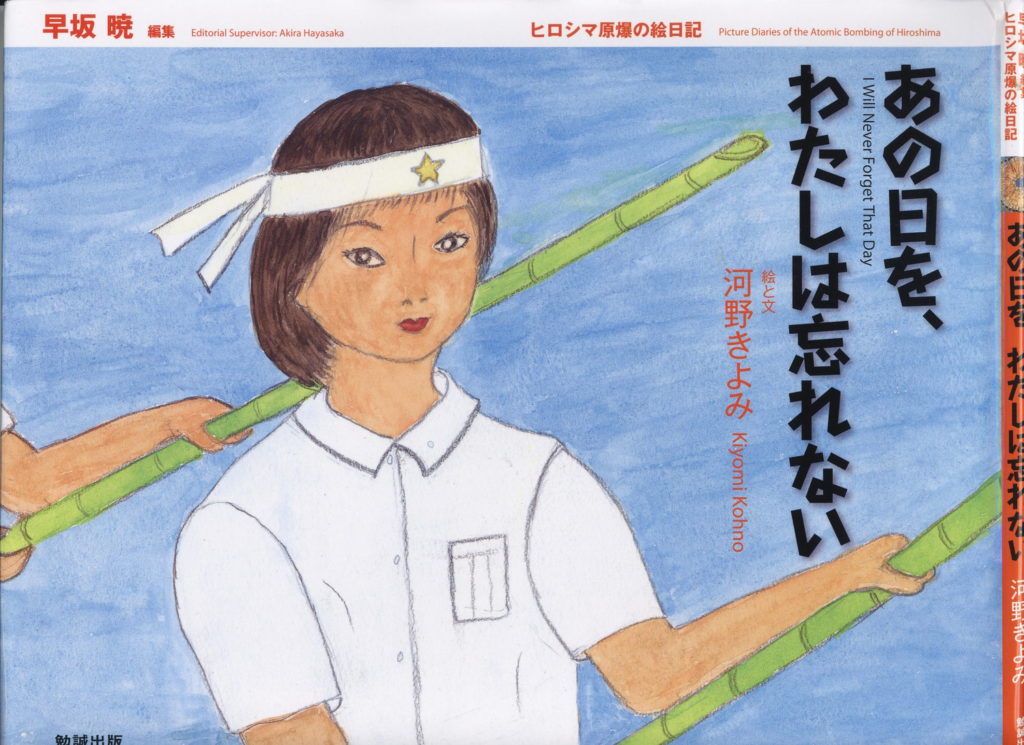

In the summer of 2007, without any notice, Mr. Hayasaka and a publisher came to my house unexpectedly with a box of sweets. They told me that they wanted to make a picture book about my A-bomb experience. I was 71 years old when I first painted a drawing, and at first, I strongly refused. However, after considering the feelings of the two men who had traveled from afar in the heat of the day, I decided to accept their request. After that, they visited many times to check on the progress of my drawings. Even though the drawings were unskilled and drawn by an amateur, in 2008, they published the picture book, I Will Never Forget That Day.

Until then, I had been so busy with work, housework, and child-rearing that I had never spoken about the atomic bombing, but I began to receive requests from people related to Mr. Hayasaka who wanted to hear about my A-bomb experience. So to share my testimony, I began to travel to Osaka and Nagano. I also received requests from overseas. In 2010, six of us, including two other hibakusha and our interpreters, were invited to speak at University of Central Missouri in the United States.

In 2013, I was part of the World Friendship Center’s PAX (Peace Ambassadors Exchange Program) and spent three weeks traveling around Washington State, Oregon, Idaho, and New Mexico. In each location, I shared my A-bomb testimony, from kindergartens to universities, and at churches and community centers. In Washington, we visited the Hanford Nuclear Site, where the plutonium used to make the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki was manufactured. Our guide told us, “In an era when there were no computers, we built a facility that could control nuclear reactors. In Fukushima, they lost the power supply and had a meltdown, but here, we had a full backup system in case we lost the power supply.” I was surprised to hear that during the same wartime period, when female students like us in Japan were training to pierce the enemy with bamboo spears, they were building such a sophisticated facility in the United States.

In Idaho, we visited the Minidoka Relocation Center, where more than 10,000 Japanese Americans were interned during World War II. I heard that my aunt was also an immigrant who was interned, but she passed away without ever speaking about it. This trip allowed me to hear about the life in internment camps, and for the first time, I was able to learn about the harsh life that the Japanese Americans had to endure. In New Mexico, we visited Los Alamos, where the research lab that developed the atomic bomb as part of the Manhattan Project, is located. There, on the shore of Ashley Pond, stood a monument with huge smiling faces of Oppenheimer and others celebrating the success of the atomic bomb.