Tsunehiro Tomoda

Surviving two wars

2.The A-bombing

The atomic bombing

To prepare for air attacks which had intensified the previous year, all 3rd to 6th graders of National Schools in the center of Hiroshima City were evacuated to the countryside. Children who had relatives living in the country were sent to those relatives. If they didn’t have any, they were taken to the rural areas by their teachers. Some children remained in Hiroshima. I evacuated to a temple in Miyoshi, the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture. Yukio did not go. In the temple, we got up at five, did the radio exercises or running, studied in the morning and worked in the fields in the afternoon. As we had severe shortage of food, we had only a small amount of rice in a bowl mixed with sweet potatoes or beans. Other food was just grilled locusts. Nothing is as awful as locusts. I hated them. As I was always hungry, I told a lie to my teacher that I felt sick. I asked him to tell my mother to pick me up. I was brought back to Hiroshima a few days before the A-bombing.

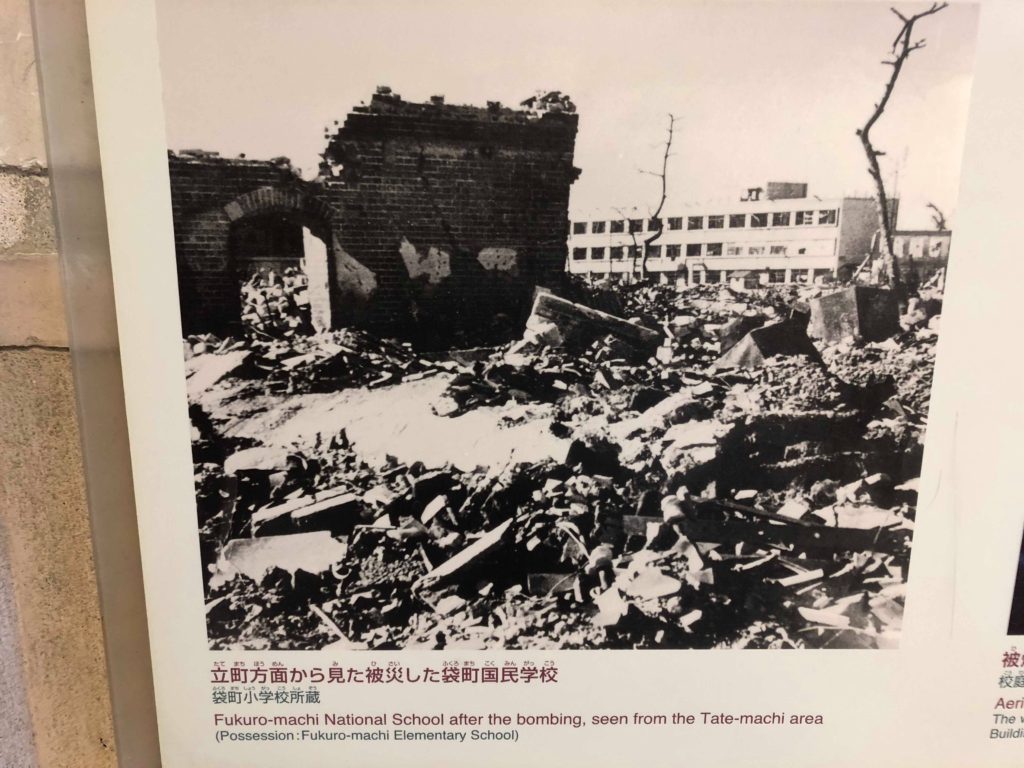

It was a fine morning with no clouds in the sky on August 6. I left my house at the same time as usual, but I headed for school playing hopscotch with Yukio. We were late for school. In front of the west building which had shoes boxes, two 6th graders always stood to watch lower-grade children. One of them pulled my arm, saying, “Hurry up!” Just at that moment, I could hear a B-29 and brushed aside his hand, thinking it was dangerous. I dashed down the steps toward the shoe boxes in the basement of the concrete building. In the grounds, there were five or six teachers and about 70 children standing in line for the morning gathering. When I put on one shoe and tried to put on the other one, there was a flash outside. At that moment, I was blown off balance and lost consciousness.

Fukuro-machi National School after the bombing,seen from the Tate-machi area

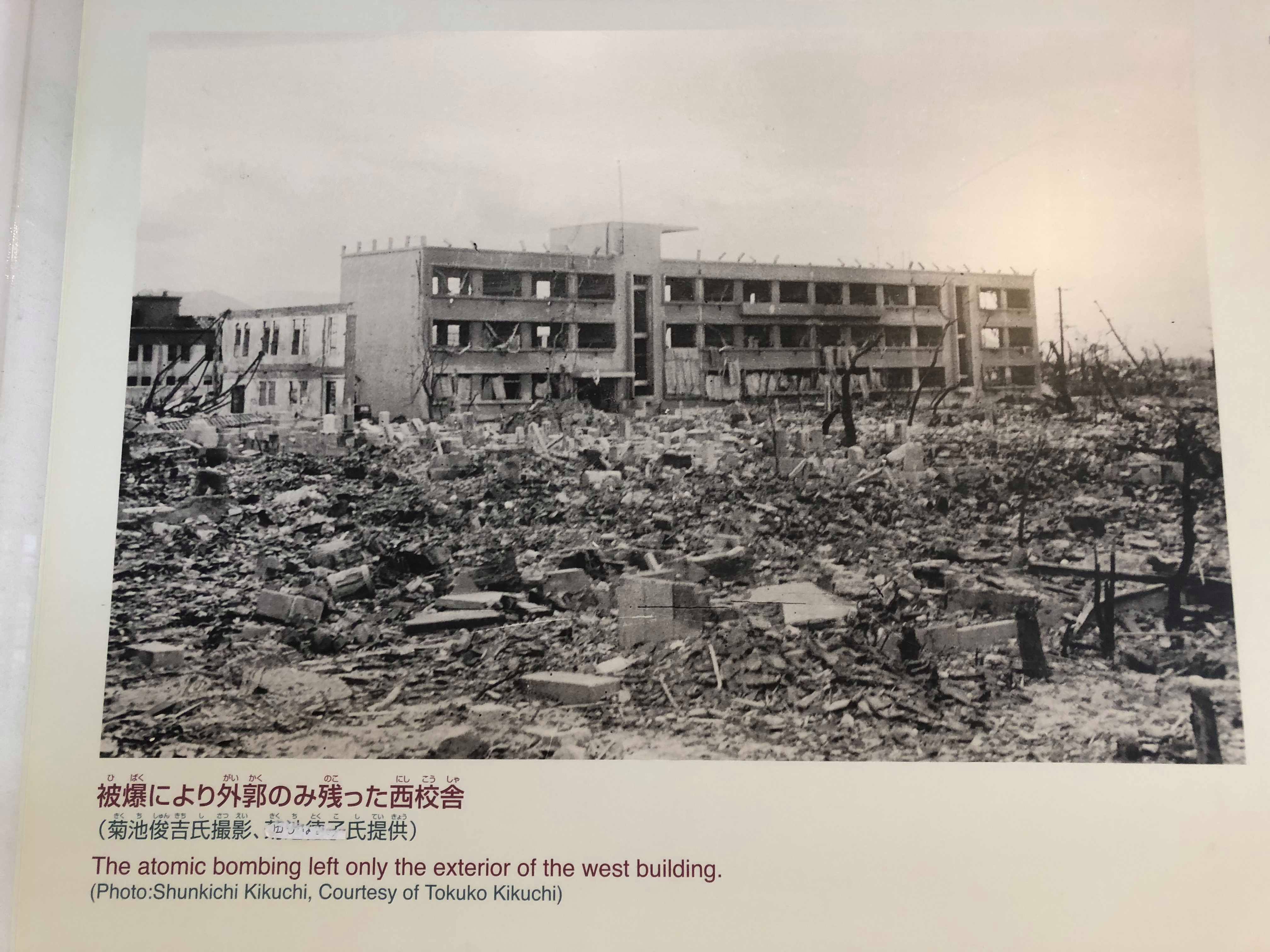

I don’t know how long I was unconscious, but when I came to, I could not see anything because of the dust and darkness. It seemed that when I was blown off balance, I might have hit hard against the wall. My back ached so much that it was hard even to stand up. A broken piece of glass stuck in my left thigh which was bleeding. My brother had changed his shoes faster than I had and went up the stairs and outside. I felt my way in the dark and managed to go out. I found a charred body on the top of the stairs. I could not identify the face or body, but I could read the characters, Tomoda, on his shoes. I realized that it was my brother. In the grounds, all the children were charred and fell down flat. For some reason, all of them had white teeth, which were conspicuous in their charred bodies. The wooden buildings which existed one moment before all disappeared and were reduced to rubble. The structure of the west building which had shoe boxes remained, although the inside was covered by ash.

I went back to the basement of the building and found Sadao, a classmate, who was still there at that time. Outside the school, many people with awful faces walked toward the east. We just followed them. Dust was whirling up and a sickening smell lingered. I almost lost consciousness many times. I saw a man whose belly was torn with his organs coming out, a woman walking with her hands in front whose skin was hanging down, a dead child trapped under the mud wall, dead people piled up, and a dead horse whose organs came out. All the buildings had fallen and we didn’t know where we were walking. We just followed the people who walked in front of us. It was so chaotic that I was separated from Sadao just after we crossed the Tsurumi Bridge. I arrived at Hijiyama Hill by myself, about two kilometers from school. Many people had evacuated there. I stayed there for three days. At night, I could see phosphorus lights here and there in the city. During those three days, people died one after another all around me. Even if they died, there were no people to carry them out. Being surrounded by people who I didn’t know if they were alive or dead, I felt scared and cried all the time. Also, we didn’t have anything to eat or drink. On the second evening, some soldiers came and gave us hardtack and water, which was the first food I ate since the A-bombing. During the three days in Hijiyama, it was the only food I could eat. But thanks to it, I could survive.

The atmic bombing left only the exterior of the west building.

On the third day, no more tears came out. I thought, “I should not stay here anymore. I have to look for my mother.” I went down the hill and tried to head for my house. However, bodies lay here and there, and I didn’t know the way back because of the debris. I walked on the wide street along the tram track to Hiroshima Station, turned west and then south following the track. I walked and walked, heading for my house near Shirakami Shrine. When I came back to the place where my house had stood, nothing remained. I could not find my mother or her body. Looking for her, I walked around the town which had ash and the stench of dead bodies hanging in the air. There were also countless bodies floating in the river. That night, I slept at the City Hall building. Many people were lying there, too. The next day and every day afterwards, I looked for my mother, getting rice balls at aid stations. I went to school grounds, temple precincts and riverbanks and checked each face of the bodies piled up there to cremate. However, I could not find my mother.

Fukuro-machi Elementary School was located about 460m from the hypocenter. It is said that almost all the people within 500m from the hypocenter died. But at the school, three people who were in the basement at that time miraculously survived. It is called “the miracle of the basement of Fukuro-machi Elementary School.” A local TV station covered this on the 25th anniversary of the A-bombing. At that time, there was a chance for the three of us to see each other again in the basement. Sadao lost all eight of his family members in the A-bombing and was taken in by his aunt in Matsue, Shimane Prefecture. I heard he became a sushi chef near Tamatsukuri Hot Spring resort. The other person, Hitomi, was a second grader at that time and lost his six family members, including his parents and brothers. Although he could see his brother and sister who had evacuated to the countryside, he was taken to the Ninoshima Gakuen Orphanage alone and stayed there until he graduated from junior high school. Then, his brother who was independent took him in and he became a staff member at Hiroshima City Hall.

Running across Mr. Kanayama

I walked around the town filled with debris every day searching for my mother. I don’t remember how many days passed after the A-bombing and where it was, but I ran across Mr. Kanayama one day. As soon as he saw me, he said, “You are alive, Tsune-chan!” and gave me a bear hug. I couldn’t have felt happier. It was exactly like manna from heaven. He was also pleased to see me and said, “You’ve survived! You’ve survived by yourself!” He took me to a place near Miyuki Bridge, next to Hiroshima University, where his Korean friends and he had been living together and building some shacks for themselves to live in. We collected materials from the debris around us and finally built six shacks. Someone among us brought an oil drum, and we made use of it as a bathtub and took turns bathing in it. There were three or four children including me, and collecting wood was our job. Another brought some rice distributed at a ration station, and another brought pickled radish, after waiting in a long line at a soup kitchen. Polishing rice by pumping a stick in a bottle was my job. Despite the food shortage, all of us cooperated with each other to live.

However, on September 17, the Makurazaki Typhoon attacked Hiroshima which had already been scorched plain by the A-bombing. Torrential rain brought by the typhoon flooded the Ota River and washed away heaps of debris. It is said that more than 2,000 people in Hiroshima alone lost their lives in the typhoon. Among the dead were those who had been wounded in the A-bombing lying in temporary aid tents along the riverbanks, those who had lost their houses and slept under bridges, including orphans, and those who had managed to build their shacks and just started their new lives. Of course, many of these shacks were washed away, too.

Our shacks were also swept away. Later that day, Mr. Kanayama decided to go back to his country taking me with him. When he told me his decision, I didn’t know where Korea was located, and thought that it would be a town somewhere we could take a train to go to. I was nine years old then. The next day, we took a freighter to Moji. He must have felt pity for me without parents, and I thought I could not live on my own if he left me behind. So, I followed him wherever he went. I stood behind him even in a toilet. The other Korean friends must have decided to remain in Hiroshima because I didn’t see any of them when I was in Seoul. But I had some opportunities to see other Korean people in Seoul who had lived in Hiroshima.